Cataloguing

To fulfil adequately the function of principal finding aid, the catalogue should hold information of two separate but related types: identification of the item catalogued (in an oral history collection this will normally mean identification of the informant interviewed and description of the circumstances of the interview) and a summary of the contents (in the sense of subject matter) of the interview. Established rules and conventions will greatly help the cataloguer in determining how to present his information, but the details of what information to provide and what format to use, are best dictated by the expectations and resources of the collecting organisation.

These two classes of information (item identification and outline description) can be satisfactorily combined in a single piece of descriptive documentation, whatever physical form that documentation may take. Catalogue cards, computer records, loose-leaf binders and other possibilities all offer advantages and disadvantages. The archive will wish to reach its own preferred compromise between such factors as economy and refinement, durability and ease of amendment, simplicity of removal for photocopying or other reproduction and difficulty of extraction by the unauthorised.

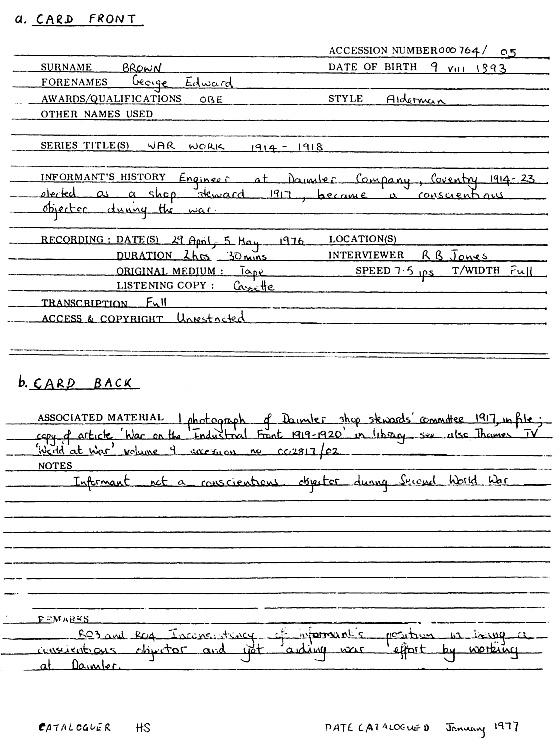

The presentation of the entry will also reflect an archive's own decisions on which elements of information are most important; how best to present information so that details often needed are easy to find; how far to reflect international descriptive standards; and so on. Reproduced [below] as an illustration (not as a model for universal adoption) is the format of a simple interview cataloguing card.

The first six lines on the front of the card identify the interview (Accession Number) and the informant (Surname, Forenames, Style, etc). An important question of principle for the cataloguer of oral history interviews is whether the catalogue entry should describe the informant as he or she was at the time the interview was recorded, as opposed to as he or she was during the period covered in the interview. Should a married woman interviewed about her single career be identified by her married or maiden name? If Daphne du Maurier were interviewed about her late husband's military career, would it be confusing to refer to her as Lady Browning? Generally speaking, the name used as a 'main entry' should be the name most appropriate to the contents of the interview and, if that criterion still leaves more than one option open, the name by which the informant wishes to be known should be preferred. All applicable alternatives should, however, be available as cross references -hence the provision for 'other names used'.

The six lines following (Series Titles, Informant's History) indicate the reasons for the informant having been interviewed. The project or series into which the interview fits is indicated; provision is made to cite more than one series title if required, as an informant's reminiscences may be relevant to more than one project. Space is also given to explain how the informant's experiences are relevant to that project. This space is left undivided, as efforts to pre-determine or tabulate 'areas of experience' will usually break down sooner or later -a format appropriate for a coal miner might not lend itself to the career of a shepherd, for example. Cataloguers would, however, be expected to establish conventions to ensure that comparable careers were described in a consistent style throughout a project. Provision of personal details about the informant and his career in the catalogue may of course be reinforced by more detailed coverage in the personal file relating to that informant which the archive will almost certainly wish to retain. The details provided in the catalogue should, however, be sufficient to indicate the topics which the researcher may expect to find in the interview.

The remainder of the front of the card describes the circumstances of the interview and its ownership. The descriptions of the information (Recording Dates, Locations, Duration, Interviewer, Original Medium etc) are largely self-explanatory, but their use is not necessarily so and serves as a reminder of the need for detailed cataloguing rules. Is the more significant date that on which recording began, or the date recording was completed? Should duration be expressed precisely or 'rounded off,' and in minutes only or in hours and minutes? What are the significant technical variables about the original recording -the type of tape (ie single, long or double play), the tape recorder and microphone used, the speed and track width of the original. If 'Listening Copy' is always available on cassette is this descriptive line redundant, or is it necessary to indicate whether or not a listening copy has yet been made? How much detail would be expected under 'Transcription' -a simple 'yes/no', or full information (Reels 1-4 and part of 5 only)? The list could be greatly extended, but the argument is obvious.

The back of the card provides space for listing 'Associated Material'. That is, material relating to the informant which is also available to users of the collection, such as diaries, photographs or letters. A section for 'Notes' allows the inclusion of additional information for which other areas of the card may not provide sufficient space or for which no other provision is made. Such information may relate to the interview (e.g. 'long break in recording owing to illness of informant') or to the informant (e.g. 'informant abandoned pacifist viewpoint on outbreak of Spanish Civil War'). The section headed 'Remarks' permits the cataloguer to record in this one area subjective comments on the interview. Such a provision will encourage the cataloguer to complete the rest of the card with proper objectivity. It also provides an extra dimension which users of the collection (properly warned of the individual and subjective nature of the comments) may find of value. For example 'surprisingly unsympathetic attitude of doctor towards shell shock' will tell the reader something about the informant which the synopsis (confined both by a restriction on length and an insistence on impartiality) could not convey.

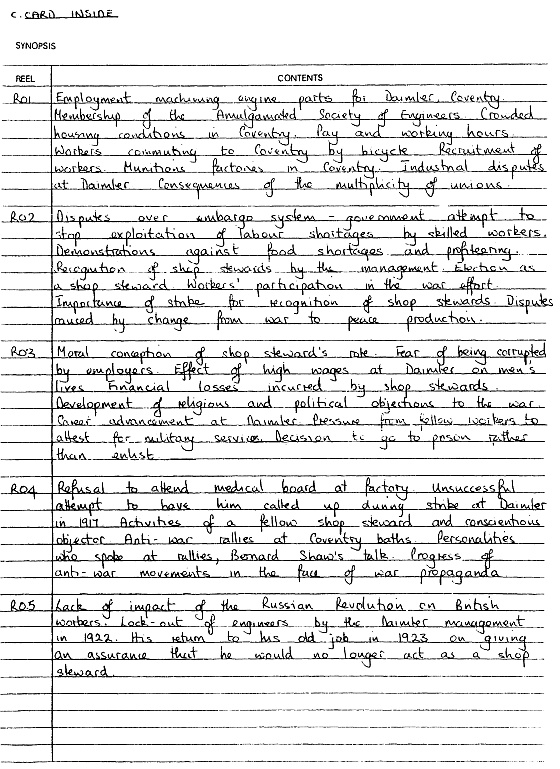

So much for the card's use to identify the item being catalogued. The second function of the cataloguing process -providing a guide to the subject content of the recording -is fulfilled by the synopsis on the inside of the catalogue card. The synopsis must be quite detailed or it will not provide potential users with as clear an idea as possible of the relevance of the recording to their interests. At the same time it must not be over-lengthy or the catalogue ceases to be an easily used research tool. The Museum's experience suggests that 50-75 words for each 30 minutes of recording strikes a reasonable balance. To compress the information contained in an interview into this number of words, and at the same time to reflect accurately the sequence or pattern of the interview, confronts cataloguers with quite an exacting task.

The synopsis should take the form of a list of the significant subjects mentioned, reflecting the order in which information appears on the tape. If an informant reverts to a topic mentioned earlier the recurrence should be noted, not deemed to have been adequately covered by the first mention. Within the limits of permitted length the synopsis should be easy to read - excessive contraction of phrases or clauses can be counter-productive. Information should also be complete: the phrase 'opinion of comfortable life lived by Italian POWs employed as farm labourers' is of considerably less use than 'resentment of comfortable life ...' The Museum's instructions to cataloguers suggest the following types of information are desirable for inclusion in a synopsis.

- Locations and dates of events wherever possible, eg 'Commission to paint and draw in Northern Ireland 1965'.

- Descriptions of events and activities, eg 'Work of wiring parties in erecting and repairing wire fortifications in no-man's land'.

- Opinions and attitudes expressed by the informant eg 'Amazement at number of pacifists' .

- Opinions the informant heard expressed about himself or others eg 'Father's hostility to her taking up nursing'.

- Illustrative stores and anecdotes, eg 'A friend losing her hand in an accident at Woolwich Arsenal' ,

- Personal recollections about other people eg 'Development of the air 'ace' concept and comments on Major T B McCudden, Captain A Ball and Captain W A Bishop'.

- Descriptions of pieces of equipment and practical experiences of using them eg 'Listening devices used for sound ranging in France during 1918. Description of microphones in use. Locating enemy guns by cross referencing signals from six points'.