Selection in Sound Archives

Selection in Sound Archives: collected papers from IASA conference sessions

Edited by Helen P. Harrison (1984)

IASA Special Publication No. 5

©1984 by the International Association of Sound Archives

[paper edition: ISBN 0 946475 02 4]

web edition published 2010

A PDF version may be downloaded for €5 from our shop. IASA members may download the PDF version at no cost. If you are not a member, why not join IASA?

Table of contents

Preface

Collection of material in an archive setting will sooner rather than lead to a necessary policy of selection.

Selection is one of the most essential elements in most archives, and selection in the archives of notebook materials is a necessity because of the volume of the material involved and the very nature of the material. Sound archives have been in existence for the best part of ninety years and the longer they exist the more necessary the process of selection becomes. Although it is an essential element and has been practiced for many decades, whether consciously or not, selection does not feature prominently in the literature of sound archives. It was with this omission in mind that IASA embarked on a series of sessions during the annual conferences dealing with various aspects of selection in different types of libraries.

This publication is a collection of papers given during these sessions. It is designed neither as a definitive statement of selection in sound archives nor as an exhaustive study but it is hoped that the articles will from the basis of a continuing awareness and development of selection principles for sound archivists to consider in their daily work statements of adequate selection policies criteria and general practice are overdue and the aim of this publication is to stimulate thought and further publication in an important topic.

The editor of the present publication acted as chairman of all three sessions at the IASA conferences and the task was eased by the assistance of those authors of the included papers who updated their own material for inclusion. A note has been appended to each section to indicate the conference at which the paper was given and the present post of the author involved. Some additional papers have been included to provide extra information or enhance the booklet with practical examples. I am particularly grateful to Peter Hart and Margaret Brooks of the Imperial war Museum in London for permission to use the criteria of selection, which were in fact drawn up partly as a result of the IASA sessions and concern in the issues involved.

The booklet begins with an extended introduction and continues with papers dealing with the theory of selection given by Poul von Linstow and Rolf Schursma. Rolf Schursma’s paper additionally enumerates some practical criteria for sound archives in general, as well as the research sound archives he specifically deals with.

Oral history is closely related to sound archivism and often provides the raw material of the archive collection. A paper dealing with criteria for selection for recording in the field is included to illustrate the particular problems involved.

Selection is a widespread problem in all sound archives, but in none more so than national archives where the volume of material deposited or available for retention enforces a selection policy on the archivist. Three papers indicate some of the problems, one from the National Archives in Washington and two from the Public Archives of Canada. One of these papers deals with the Public Archives intake of radio broadcast material. This leads directly to the radio or broadcasting archives where the volume of material constantly threatens to submerge even the most rigorous selector of archive material. Examples of broadcasting organizations are taken from England and the Federal Republic of Germany.

Two papers have been included from the session on the selection popular music, and although they deal primarily with the indexing systems in use in the two libraries concerned they also indicate the selection policies which are in force to make the collections in the very prolific area of popular music more manageable.

The book concludes with a case study taken from one collection, the Imperial War Museum in London, England, which has attempted to draw up criteria for selection. Although many archives have their own methods of selecting material, much has yet to be formalized and written down for the benefit of other archivists. The Imperial War Museum criteria represent a step in the direction of greater exchange of ideas and information in this important area, and it is in the hope that this is only the start of the debate that the present volume exists.

H.P.H.

Preface to this web edition (2010)

This IASA Special Publication, originally published in 1984, has been out of print for a number of years. Nevertheless, many of the papers have remained relevant to this day, so as a service to audio-visual archivists, we have decided to republish them in web form.

Readers should be advised that some statements in the following papers may be outdated. When this compilation of papers was originally issued, analogue formats were used universally for archival preservation copying, and many archives still relied on paper-based catalogues. Today, analogue formats are obsolete and computerised records are the norm. Among broadcasting institutions, large-scale digital storage allows archivists to retain their entire broadcast output, reducing the need for selection. An increasing proportion of collection items in audio-visual archives are born-digital, opening up the possibility for completely automated selection, handling and management of items for archival retention, once the initial selection parameters are set. For most archives, however, selection for acquisition of legacy analogue carriers and of digital items is an ongoing process. We hope you find this selection of papers useful.

International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives

June 2010

Introduction (Helen P Harrison)

Selection is arguably the most important and at the same time the most difficult of all the activities of the archivist, curator or librarian, especially those dealing with audiovisual materials. It is an essential element of the archival process and imposes a discipline on the collector almost from the beginning. A collector may not normally consider selection immediately, but the very consideration of what to collect or how wide a range of material one includes in a collection is one of the first principles of selection.

As individuals we are constantly making selection in everyday life, and most of our everyday decisions are forms of selection - shall we take one course or another; go here or there; work, rest or play. Decisions are taken almost unconsciously according to whim or circumstance. But selection takes decision making much further than this. It is usually based on a set of principles or guidelines although such principles may never have been itemised.

Collectors of sound recordings may have their own predilections or whims and this is not to denigrate their purposes, for without collectors there may never have been the basis for libraries and archives of materials.

However collections grow and very soon some process of selection, or discarding becomes necessary. The very volume of the production of sound recordings begins to demand a selection process and this is the point at which problems begin to be apparent.

The collector may be working within his own parameters of cost and space and it is his own decision as to what is kept and what is disposed of by exchange, sale or destruction. Others may question his decisions but are not in any position to criticise unless they do something positive to assist in the retention or preservation of the collection in part or whole.

Where the archivist (and for archivist one should read archivist/librarian in the context of this introduction) meets his problem is in the sensitive area of selection. A collector can be subjective in his approach, but an archivist should be seen to be objective and a selection policy or set of principles is needed here to provide a framework for collection.

Why Select?

The volume of output makes selection inevitable. As well as the commercial production of the recording industry we have a large non-commercial output and the output of oral historians and broadcasting output where far more material is recorded that transmitted and the unedited, untransmitted material may be potentially valuable for later usage. Specialized subject collections may also contain recorded material or the archivist may have conducted interviews, which have been edited down for public access purposes, but the unedited material has its own value. Following from this argument we might also consider one area often overlooked, which is selection at the point of origin. The recordist or sound archivist who initiates a recording needs to reflect on why he has to record this material, at what length he should be doing so, whether or not he should edit the recording and then dispose of the material which is superfluous to the recording he intended or his present requirements.

Selection has been made even more imperative as a result of the increased ease of recording. As tape recording has become easier and the equipment less cumbersome more and more recording is made possible by a greater variety of people. No longer is it the sole province of a technician to record material for preservation purposes. With improvements in equipment and ease of handling such equipment to produce acceptable recordings, more and more people are recording material which can be regarded as a useful record.

The real purpose of selection is to reduce an archive or collection to manageable proportion. The plethora of information and material can quickly get out of hand and unless selection principles are used we are in danger of sinking without trace in a tangle of magnetic tape, under a sea of books, cassettes, videodiscs or computer software. Worse we might disappear altogether into the computer hardware in search of that elusive piece of data, which was not properly labelled.

And herein lies another powerful argument for selection. If we do not select with reasonable care then what is the point of spending resources of time and money documenting, storing and preserving material, which is not of archival value?

Indeed it is a dereliction of our duty as information providers, whether archivists, librarians or information scientists not to select the material for preservation and future use. Too much information can be as difficult to handle as too little – it is equally difficult to access and discover the material, which would be most useful. The idea that you can, with the aid of modern technology, store everything easily on those convenient little cassettes appeals to the research worker, but how on earth does he think you are going to access a roomful, and it has been expressed in that very term, of video-cassettes and audiocassettes, each cassette bearing up to 3 or worse 6 hours of material, not necessarily in edited form. The research worker forgets that someone has to expend effort and time entering the information on to the database in a retrievable or accessible order.

There are inevitable constraints placed on any archive, which make it necessary to adopt selection policies. These constraints may be basic and arbitrary ones such as space for storage or the high cost of storage, or they may be constraints imposed by the available resources in terms of people and time as well as financial resources to prepare the material for storage, conservation and subsequent access.

As stated already, but always worth repeating, archives are not simply repositories. Some form of records management is essential to impose an order upon the record and make it manageable and accessible to future users of the archive, whether these users are researchers, browsers, those with a commercial concern to reuse the material or interested members of the general public.

Records management is about human resources. Without management of the record and the intervention of people the repository of sound recordings would probably deteriorate and certainly it would become difficult to locate particular items or groups of items within a very short space of time. There is of course merit in acquiring as much material as possible in a particular field of interest, especially in the early stages of development of a collection, but once acquired it is bad practice to leave such materials in an unordered state. The archivist has a responsibility to the material itself as well as his “user”. The material needs processing, filing in a retrievable order, conservation, and some form of information retrieval, however basic, should be imposed upon it as soon as possible after acquisition.

Selection may be a more leisurely process, but it is nevertheless a necessary one and should at least be considered from the outset. It need not happen immediately, but with any volume of material the need for it will quickly become apparent.

Archivists are not simply store-keepers. They must impose a discipline of management on their collections, and one of the more important disciplines will be the selection process. Selection, like management, is not an exact science. If it were then the archivist might have exact criteria and theorems to guide him. Nor do I believe that selection is an art. It can be argued as more of an art than a science, but I would prefer to consider selection as a craft, practised to achieve certain ends with suitable criteria or guidelines to meet these ends.

Purpose

If the first principle of selection is to reduce the collection to manageable proportions, the purpose of selection is to ensure a balanced, representative collection of material relevant to the nature of the subject matter of the archive concerned. This means different archives will have different selection policies according to the intended use of the collection. Selecting material within areas of interest of the individual archive immediately raises the question of what is in the field of interest and what is outside? There will, almost inevitably, be grey areas where the material could be considered of use to the archive in conjunction with the rest of the collection. Rigid criteria are thus going to be of little use to the archivist; criteria must be flexible and try to take account of the related areas of interest.

Who Selects

Given the guiding principle that selection is of necessity one of the first major concerns of the archivist it will be necessary to establish who it is who is to select the material and then formulate the criteria for selection. Let us start with who is to select the material deposited in the archive. Some archives have selection staff who concentrates on the areas of acquisition and selection. Some archives use a system of selection committees, usually an ‘ad hoc’ arrangement whereby committee members are made aware of likely items of interest, or debate the merits from a listing supplied by archive staff. Such systems normally depend on the subsequent availability of the material and cost of acquisition. A lot of material escapes the net by this method of selection, but it does nod in the direction of consultation.

But is selection by consultation and committee necessarily a good thing? It is fraught with difficulty when sectional interests appear and squabbles break out between people from different disciplines. A short piece paraphrased from a book on Archive Administration written in 1922 by Hilary Jenkinson serves to make the point;

“The archivist is concerned to keep materials intact for the future use of students working upon subjects which neither he nor any one else has contemplated. The archivist’s work is that of conservation and his interest in his archives as archives, not as documents valuable for proving this or that thesis. How then is he to make judgments and choices on matters, which may not be his personal concern? If the archivist cannot be of use, can we not appeal to the historian - he may seem the obvious person to undertake such a task. As soon, however, as the historian’s claims in this connection are investigated it becomes clear that the choice of him as arbiter of the fate of archives is at least as open to criticism as that of the archivist. Must he not be regarded, where his own subject is concerned, as a person particularly liable to prejudice? Surely there will always remain the suspicion that in deciding upon a policy of archive conservation he favoured those archive classes, which furthered his own special line of inquiry. The very fact that a historian is known to have selected for an archive is fatal to its impartiality”.

Some of the more curious suggestions about retention of material, which have been encountered, come from eminent people in their own fields who want everything kept ‘in case they need to study it’. Why do they want to study it? Uncharitably we could suggest in order to select information for the benefit of the rest of us, but more seriously any archivist would wonder that they have the unlimited time at their disposal which is needed to sit through hundreds of hours of material.

It would appear that selection should be done by the archivist or librarian and not by outsiders with peccadilloes and sectional interests. Specially appointed staff in the archive can see the wider implications and, if thoroughly versed in the aims and objectives of the particular archive, are in a good position to select. But to be effective they must be carefully chosen and they should have a set of criteria to work with.

Criteria

The purpose of this publication is to indicate possible criteria for selection in different archives. There are several governing principles, which should be considered before guidelines can be enumerated.

Principles

-

One mentioned already is that the archive selects material according to the needs, purpose and intention of the collection and with the ultimate ‘user’ in mind. Subject areas of interest may be narrow, but the related or ‘grey’ areas should not be overlooked in selection.

-

Material for archival preservation should be either unique to a collection or not duplicated in several existing collections where there may be a waste of resources preserving the same thing three or four times over. Legal deposit is a rarity and one archive cannot assume that any other is collecting in a particular area or country of origin. In these circumstances it becomes important for all sound archives to have selection policies and to discuss their policies with other archives both nationally and internationally and ensure that valuable material is kept somewhere, but not in each and every archive. This is one of the main reasons why the International Association of Sound Archives was formed.

-

Quality. This is a relative principle; closely related to the unique quality of the material. In theory the best quality material should be selected, but sometimes, when the only available material is of poor quality, its unique nature overrides the principle of quality. A closely related factor is that of technological change which may mean a recording is only available on an ‘obsolete’ carrier. Archives should not select on the basis of whether or not they can replay material - this is library selection, when the only material in a library relates closely to the playback machinery available either in the library or in the user’s home. An archive must consider other qualities of the material and if it is essential to the collection, but on an unplayable medium, an archive needs facilities to transfer it to a usable medium.

-

Some material may be ‘unusable’ because of copyright or contractual restrictions. However, copyright can lapse and one of the functions of an archive could be expressed as outliving copyright and other such restrictions. The material is held for the restricted period (it may even be possible to use it under certain conditions during such a period) and then, when copyright is released, the archive will be able to grant access to valuable material. Copyright restrictions should not necessarily deter selection of valuable items and the selector must think beyond the temporary restriction.

-

The timing of selection is also an important principle. It should never be a once-for-all decision. Some material need be kept for only short periods while checks are made on existing material which it may duplicate. Other material can be looked at retrospectively after a period or periods of time. Most archives, which practice selection, will be found to use this principle.

An archive will collect material in accordance with its purpose and objectives but, as these may change at intervals, the selection principles will have to be flexible to accommodate these changes. Selection principles should, therefore, be subject to review.

- One of the main principles of selection is objectivity within certain guidelines. Selection staff should be as objective and free form bias as possible within realistic parameters. Hindsight is a useful mechanism here and it can be achieved by adopting a long-term policy of selection. Optimum selection decisions are best taken after a ‘decent’ interval.

These principles are not of course criteria for selection, but they include many of the considerations the archivist should take into account in formulating his own criteria for selection.

The rest of this publication will expand and elucidate many of these principles and indicate how practice and practical considerations affect them.

The criteria for selection of sound recordings have not been, and indeed cannot be laid down as hard-and-fast rules, but it is hoped that the readers of the book will find many practical examples and working principles in the pages which follow; examples of criteria used in different types of archive with particular purposes which will assist the profession of sound archivists to arrive at reasoned, practical criteria for selecting material to store in archives for passing on to future generations.

IASA has recognised that selection is a central area of the archivist’s concern and this series of papers exists to continue the debate about criteria or guidelines for selection; a debate which may rumble on for some time. In highlighting the problems we can only hope that our successors will recognise that we took notice of an obligation to select, and even if they may quibble over what was selected or destroyed, will be grateful for the production of more manageable archives.

Helen Harrison is the Media Librarian at the Open University in England. This paper is an extended version of the brief Chairman’s introduction given at the IASA conference in Budapest, 1981.

Philosophical and methodological aspects of Selection (Poul von Linstow)

Introduction

As a widespread phenomenon sound-archives have not been in existence for very many years compared to other types of archives and collections from man’s past. We have only just started to realize some of the problems which other forms of collections have had for many years; for instance the problem of preservation, and problems in connection with the rapid growth of collections in modern times. Suddenly, the collections may - for different reasons - be considered too large, awkward to handle and too difficult to use.

We all know - or have a clear suspicion - that audiovisual materials are much more difficult to preserve than documents. The cost of preservation may in the long term be so large that the necessary resources cannot be raised. Utilizing material in the archives, in research, in broadcasts or reused in the form of sound- or video-cassettes will for many subject-groups become a problem, because of the sheer size of the collections. It is not only limited space that causes us to declare the collections too large - audiovisual material is very, very slow to work with, and one can fear that some research-disciplines will give up using audiovisual material to answer traditional problems and questions if unreasonable amounts of time have to be used referring to audiovisual material compared to other forms of source-material. This problem should not be underestimated. The type of questions which the users of the archive expect an answer to after investment of a reasonable amount of work, will degenerate into simplification and end up in becoming irrelevant for serious research, if the collections are too large or confusing.

Up until now we have only seen the beginning of a selection-debate within the realm of sound-archives - and have been spared the merciless necessity of radical selection until now. This is the beginning of a debate which will last for many years and which will be constantly reformulated in connection with technological developments, changing types of users and economic development. The debate will be intensified and we will hear echoes of it every year at IASA conferences and many articles about the problems in the Phonographic Bulletin.

The problem of selection has many aspects and it can be discussed in several ways. It is of course impossible to solve the whole problem in one short session. This paper will, therefore, concentrate on a somewhat over-looked aspect; namely how selection is conceived of philosophically and methodologically. What kind of philosophical conception offers the best interpretation of the general structure in the selection process, and what type of methodological conception can, in the most fruitful way, be used in analysing the details of the selection process?

A Concrete Example

In the first place it is necessary to create a clear image of a selection process, because it is the image, which is the starting point of the analysis. It is not unimportant what kind of selection process you imagine. Some archives have very rigid selection-typologies - so rigid that it is almost meaningless to speak of selection - and other archives take everything they can lay their hand on. It is clearly unfruitful for our analysis to take such procedures as a starting point. It is necessary to build up our image from elements of a selection process which is reasonably free from rigid selection-typologies and at the same time considers it absolutely necessary to make rather thoroughgoing selection. When one is investigating philosophical problems it is important not to get lost in practical problems - we want to analyse the structure of the selection problem, and to that end it is necessary to construct a kind of ideal-typical image of the selection process - ideal-typical in the sense that the image consists only of elements in the process which are relevant for the analysis. The ideal-typical cannot be found in any existing archive but, nevertheless, our construction of the image has to originate from a knowledge of existing archives. I will, therefore, describe very briefly the selection process in my own archive and thereafter, you must supply this image with elements from other archives, which are known to you. In short: we want to create an image of a ‘clean’ selection-process, and in this creation or construction we only use the elements which characterize and accentuate the structure in the process.

The archive used as an example is Radio Denmark’s archive for spoken word and non-commercial music. The only principle we need to take into consideration in our selection of material is ‘possible re-use in radio programme production’, and as radio programmes are being made about almost everything - or at least one can imagine so - we are relatively free from rigid typologies. But we are restricted by the fact that if the collections become too large, they will at the same time become unfit for programme production - a problem which is normally greater for journalists than for researchers. 95% of the material is actively selected by archive staff and the selection is based on short descriptions of content which are sent to the archive from the programme production departments, including television when the sound track is sometimes relevant for our collections. Every day we receive these short descriptions of content covering about 50 hours of production and we select on average 5% from the large number of complex problems being treated in a nation-wide non-commercial broadcasting station. The intention of selection is that the material shall contain the essence of the subject and its treatment; and that, of course, cannot be done by selecting some ‘objective’ percentage from news and cultural relevant programmes - in fact it is a question open to debate as to whether ‘objective’, automatic percentage-selection deserves the name ‘selection’ - rather it should be called ‘sorting’. The selector is supposed to possess an educated problem-consciousness - an education which not only derives from knowledge of the radio-medium itself and its specific way of treating the problems, but also from independent and thoroughgoing knowledge of the problems essential and characteristic of his own time and our knowledge of man.

In Radio Denmark the selection procedure is mainly founded on one staff member who examines all the radio and TV programmes each day. After this first examination the selected material is secured by other persons such as technical staff and the programme departments themselves - but the important thing here is the principle - one person/all the programmes - which forms the corner-stone of selection in Radio Denmark. One of the advantages of this principle is that it makes it possible to build up the collections systematically around essential themes and developments in the medium. For example, all the small but perhaps important elements from news and magazine programmes are examined in the selection procedure. Separately they are perhaps not relevant for the archive, but if systematically pieced together they can be used in the future description of many important problems, some while ago in Copenhagen there were episodes in connection with young people who illegally moved into empty houses. Several programme departments, both television and radio, reported these episodes, which were rather interesting in bringing into focus otherwise unrealised problems. But the reports where only given as short items in magazine and news programmes, and they would have been lost if selection was limited to the large, unique programmes. This is often the case if the programme department has a monopoly of selecting material for the archive. One problematic point in the procedure is that the basis for selection is short written summaries. To what extent is it possible to use written abstracts as a basis for selection of audiovisual material? Another facet of the selection process, which cannot be covered in this paper.

To sum up, the process of selection can be described as follows. Each day short abstracts of about 50 hours of transmission are received representing about ten pages of written abstracts. On average you must select five per cent and it must happen in such a way that the selected material does not give a passive reflection of the broadcast material. The selection ought to be active and creative, so that new problems can be treated and researched in the selected material.

The next step in the analysis is to move from this newly created image of the selection process to a precise formulation of the selection problem itself

The Problem Of Selection

Formulation of the problem is of great importance to the kind of answer arrived at in the end. The formulation of the problem depends on the purpose of the analysis, and the purpose is to reveal some essential logical structures in the selection process. We are now moving into a broad and difficult field within theory of science, it is the field concerned with the relationship between general or ‘nomological’ knowledge and concrete, ‘ontological’ knowledge. This relationship between general, nomological knowledge and concrete, ontological knowledge is basic to understanding that the sciences are composed of a systematic, ‘law-seeking’ part, and when trying to use a science to investigate specific, practical problems and events. This can be applied to most of the sciences; theoretical physics being used on practical problems, for instance, Newtonian mechanics can be used to calculate the time for a specific solar eclipse, or other general physical laws can be used in specific weather forecasts, or theoretical economics can be used to explain specific economic events; or within our own archival realm, a generally formulated selection-typology or subject-typology can be used to decide whether a specific recording is to be selected or erased!

But a subject-typology is not scientific ‘knowledge’; and there are other differences. However, the structure of the problem of the relationship between a generally formulated subject-typology and a specific, concrete decision to select or erase is the same as in the just mentioned sciences. Of course this does not mean that a decision to select or erase has the same degree of precision as an astronomical calculation of the orbit of Halley’s comet; a comparison between selection-decisions and weather-forecasts might be more proper. Selection is not, and cannot become, a science in the classical sense of the word - but the structure of the problem of the relationship between general and specific knowledge is identical in the sciences and in selection-work. When the structure is identical, then we are permitted to use the available philosophical and methodological scientific literature in so far as this literature is concerned with the structure of problems and not for instance with the nature of the objects to be analysed. Before taking up these matters it is important to solve the formulation problem, or rather the two interconnected problems, which appear in the selection process. As it is in the sciences, the case in our archival interest of knowledge is split in two different ways of thinking. One of these is systematic and general and is concerned with the formulation of the archive’s selection-typology or subject-typology, and the other is concerned with the problems of the specific decisions of selection. The selection problem can be formulated as follows: the problem of selection is the problem about the interconnection there is or ought to be between the more or less explicit general subject-typology and the specific selection-decisions. The subject typology need not be explicitly formulated-in a way it is just our general conception of what ‘ought’ to be selected.

The Subject-Typology-Epistomological Status

An example of a short subject-typology could be:

- Material of interest for contemporary history,

- Biographical material concerning known personalities,

- Ethnologically and culturally interesting material, and

- Material of interest for the arts.

Now, one can ask, what is the condition of possibility for creating such a typology? What must necessarily be known before the typology can be formulated? The answer to these questions is of course that it is necessary to have a more or less conscious or clear conception of what it is essential to know about man, combined with a conception of the way in which the audiovisual material in the archive can be expected to contribute. Some of the most important aspects of the problem of selection are to be found in the thinking connected with formulation of the subject-typology. The distinction between essentials and inessentials, which in the typology is formulated in a general way and in relation to the archive’s purpose, rests on criteria derived from conceptions of a metaphysical character such as conceptions of ‘man’, of ‘society’, of ‘culture’ etc. It is in these concepts, which in our knowledge and actions work in a heuristic and not a deterministic way, that our personal ‘philosophy of history’ or our personal ‘metaphysic’ are to be found. All these concepts are often very vague and only partly consciously analysed, but nevertheless they are necessary and form the basis for our image of world. They are a kind of a priori, torso-like, but absolutely necessary total-image of our life-world, and in reality it is this flickering and unanalysed image, which is fundamental for our thinking knowledge, when we act, and when we select. It is the flickering, metaphysical image, which is behind both the formulation of the general subject-typology and the specific selection decisions. In the typology the image has been formulated in a general way - in the specific selection the image has the character of a heuristic basis for a decision. Everyone who has made decisions about essential/unessential has to find his arguments in these metaphysical conceptions if his selection decision is being criticized and therefore needs some kind of argument. It is an eventual critique, which makes clear the metaphysical character of selection work - and metaphysics does not mean pseudo-religious conceptions, but the common principles and concepts, which create coherence and integration in our thinking. Coherence and integration are the key words!

It can be seen therefore that the problem of selection is founded one kind of metaphysics; but it also has other philosophical aspects. One of these lies within theory of knowledge. One could say, that the metaphysical part of the problem is concerned with the answers to the question: what are the conditions of possibility for selections - what is the a priori in selection? But the theory of knowledge problem is concerned with the answers to the question: why must this material be selected and that erased? It is the structure or logic of thinking in practical selection work we are looking to find. How does the selector motivate a specific selection?

At this point the discussion can take advantage of the previously mentioned debate about the relationship between general and specific knowledge, between nomological and ontological knowledge. In the space available we can mention only a few elements in the dominant conception of the problem and some of the points of critique. The dominating school is positivism, and it is the positivistic conception which underlies what many Americans call ‘hard’ science’.

The literature about positivism is very large, but a classical representative is Carl G Hempel, whose articles The Function of General Laws in History, (1942) and Studies in the Logic of Explanation (1948) are worthy of reading. In short, the positivistic ideal is, that when you must explain an event, then it is necessary to split it up into several parts, so that every part can be explained by means of the general laws formulated within secure sciences. If, for instance, you must explain a specific traffic accident, the first thing to do is to establish the experiential data; influence of alcohol, braking distance, the specific traffic situation, mental condition of the driver, etc., and then you will investigate these data by means of the relevant sciences, which in the case will be: medical science, technical science, traffic-sociology, psychology and so on. The general knowledge from these sciences, which can be used, is called ‘covering laws’ because they are considered to cover the established facts. After the analysis of the facts by means of the respective sciences, the positivist nominates the sum of these separate explanations to be the explanation.

The same kind of procedure is involved when a selector motivates a specific selection by referring to it being ‘covered’ by one or often several categories in the subject-typology of the archive. But this kind of explanation suffers from great weaknesses and the critique of positivism is about to uncover some of them. A brief critique of positivistic theory of knowledge can be found in Maurice Mandelbaum’s article: The problem of covering laws, in History and theory, (1961), and a very profound critique can be found in one of the most exciting, modern philosophical works, Bernard Lonergan’s Insight. A study of human understanding, (1958).

The starting point for Lonergan’s theory of knowledge is the analysis of the event, which we call an insight. He is not interested in insight as a psychological phenomenon, but analyses the character of the increase of our knowledge, which is involved when we get an insight. For Lonergan it is, so to speak, the insight, which is the atoms of knowledge – for the positivists the atoms are verbally, formulated, elementary statements about what is considered the reality. There are of course many problems involved in this, but the point is, that the positivistic summing up of their many separate explanations involves an insight, an epistemological operation, which is overlooked by the positivists. The separate explanations of the mentioned traffic accident are: influence of alcohol, bad brakes, bad traffic conditions and a depressed driver, and the positivist considers it unproblematic to put a circle around all these separate explanations and to nominate the sum: The explanation!

What is overlooked is that the circle or summing up involves an increase of our knowledge, and therefore it must be motivated. The positivistic theory of knowledge is unable to motivate the summing up! There are perhaps secure sciences which can be used in explaining the separate parts of the event - but there is no science which can explain how the specific parts of the event are integrated again; remember the key words are coherence and integration! The positivistic theory of knowledge will only be able to create explanations in the form a long string of possible separate explanations. In the same way, a positivistic selector can only motivate his specific selections by referring to this or that point in the explicit subject-typology of the archive - that is the reason why a positivistic selector always has an explicit and very detailed subject-typology: he simply cannot live without it.

In short, the problem for the positivist is, that his theory of knowledge does not include principles by means of which coherence and integration can be created. In practical work there are no differences between a positivist and a non-positivist. The difference is in their philosophical and methodological understanding of what is involved in their practical work. To the positivist, the integrating principles of coherence are ‘unscientific’ or ‘subjective’ and are, therefore, not included in his theory of knowledge. But the selector with a fully developed self-awareness will recognise the integrating insights, which are involved as a necessary part of his work and these integrating principles are exactly the same metaphysical principles, which have been mentioned before. It is, therefore, a self-delusion to believe that a reference to some selection-typology can be used as a proper motivation for selection - unless of course the typology is so restricted that the problem of integration does not exist. Then the positivistic understanding can be used, because no integrations of separate explanations or motivations are involved. If, for instance, the archive must select every kind of material on a certain person, then it is obvious that the motivation problem does not exist. However, in that case the question remains as to whether selection is involved at all.

The problem of selection has only been solved in a very general way in the formulation of the archive’s subject-typology. The kind of general solution of the problem in the subject-typology cannot be directly used to solve specific problem of selection. Often you will have a feeling that the selection problem is buried in the typology. For instance, the typology contains the category ‘contemporary history’, but within this very category there are essentials and inessentials. And furthermore, the category contemporary history cannot be defined in relation to history as a science. It is defined in accordance with the nature of audiovisual material or the needs of the programme producing departments. This means that the criteria traditionally used in the science history cannot be directly applied. A typology can only in a very restricted sense be used to solve specific ad hoc selection problems. It can be used to give potential customers a general idea of what can be found in the archive, and it can be used to define in a formal way the working-purpose of the archive. It can also be used in the selection of material, which may be unambiguously described as in a particular category.

Application of a general typology presupposes an integrated insight into the elements of the specific problem of selection. Otherwise you will not be able to discover that the typologies or categories are involved in the specific problem - and in the same way you are unable to discover the specific integration of the categories. In short, the application of a general typology needs interpretation in every specific selection decision. The typology is only one out of several factors involved in specific selection work, and it must be stressed that the typology itself does not contain principles by means of which the integration can be motivated. The principle of integration is to be found in ourselves in the form of the aforementioned heuristic, pre-scientific, but necessary total-image, which is activated in the meeting between the selector and his specific selection problem.

Therefore selection is a kind of metaphysical achievement resulting in a creative, integrating insight and decision, and it is founded on a complicated combination of our more or less conscious and educated total-image, explicitly formulated general subject-typology and understanding of the specific selection-problem involved. Selection is not in the category objective, secure, hard science, but in the category meaningful, subjective action. For that reason a selection decision will always have to live with the possibility of being questioned. The selection decision is not a science but an action, which is open, creative and perhaps even playful - and long may it continue to be so. Objectivity in selection, for instance in the form of percentage selection or the impossible (in the long run) total selection will transform archives into stores and the creative, educated selection into automatic, mechanical sorting.

Therefore, in reply to the first of the two questions raised in the paper’s introduction, I am of the opinion that the problem about the philosophical conception of selection is best solved by conceiving selection as meaningful subjective action, always open to debate, and as a philosophical method I would recommend self-awareness in relation to the practical selection work based upon the epistemological phenomenon insight as understood by Bernard Lonergan.

The second question, which was raised in the introduction, concerned the methodological conception of selection. The problem has only been touched upon and space decrees only a very brief mention of the research-discipline, which will be staid the selector to make his practical work transparent. What I have in mind is the decision-making theory.

To recapitulate, I tried at the beginning to show the presence of a kind of metaphysical heuristic total-image, our subjective-reality, as a foundation for selection-work. This image was formulated in the general subject-typology as a description of what categories of material the archive must select to fulfil its purpose. The general subject-typology has the character of a normative description, however specific selections are not description, but decisions! The typology and the specific selection are two different ways of thinking about the same problem and that is why the problem of essential/unessential seems buried in the typology when you try to motivate specific selections by means of the typology. The typology is not a set of rules to be followed blindly; rather it is a kind of framework for creativity. The specific selection is a creative decision, and it is of course unwise not to use the large literature about this subject to reach a more profound understanding of what is involved in decisions.

Some of the fundamental works within the discipline are to be found in the general action theory, but the most directly usable works are strangely enough to be found in the special elaboration of the theory for analysis of political decision-making. Richard Snyder, Graham T Allison and John D Steinbruner ought to be mentioned and if you are interested in analysis of the concept meaningful subjective action, Alfred Schutz ought to be consulted. Space forbids me to enter into details of decision-making theory, but the self-understanding of the selector will be much improved by studying the decision-making theory’s analysis of the many very complicated factors involved in decisions, from the cultural blind spots, through the organisational forms of the archive itself and on to the individual psychology of the selector.

Understanding these factors cannot, of course, make selection objective but it can make the selection decisions less arbitrary - and the selection debate can profit from the definitions and the very differentiated concepts within the decision-theory. Another problem, which can be illuminated by decision-making theory, is the problem of differentiating between types of selection. Earlier in the paper I outlined the type of selection in my own archive, but there are of course a lot of other types - one of them I have referred to elsewhere as sorting. In the decision-theory there are at least six different paradigms or types, each of them characterizing a type of decision. For instance, there is an analytical paradigm, a cognitive paradigm and a cybernetic paradigm - the last one can, with advantage, be used to characterize the very simplified and automatic form of selection, which I have called sorting. But these differentiations and refinements will come in connection with the intensified selection debate, which we can expect in the years to come.

Poul von Linstow is the Radio Archivist of Denmark Radio, Copenhagen.

This paper was given at the Brussels Conference in 1982.

Problems of selection in research sound archives (Rolf Schuursma)

An archivist is usually the opposite of a selectionist….

This was the first sentence of a paper, which I presented to the Annual Conference of IASA in Jerusalem in 1974 (Phonographic Bulletin, No. 11, May 1975, P.12-19). The paper was called “Principles of Selection in Sound Archives” and it is perhaps symptomatic that the focal point of the present contribution has moved from principles to problems. Since 1974 I have been involved in various efforts to cope with the ever growing amount of sound and film records in the Netherlands, and again and again the term “selection” has appeared as a kind of incantation - a miraculous keyword - which should open the road to archival happiness. In fact, selection means a lot of problems, which mainly have to do with a lack of funds and, most particularly, with a lack of staff. This paper does not attempt to provide the final solution to our troubles. It is meant as a stimulus for discussion and a starting point for critical questioning about archival policy. It is primarily restricted to the problems of spoken word collections, but some observations might also refer to archives of music recordings, and even film and TV archives could easily recognize some of their own deliberations and solutions.

This paper will summarize statements made in the 1974 conference about selection criteria, and the then draw attention to the process of selection and the effectiveness of selection.

In the context of the paper, ‘record’ means the carrier, including the audio-information. ‘Recording’ means just the audio-information itself. So a gramophone record or an audio tape is a ‘record’, containing for example a ‘recording’ of an interview with Bela Bártok or a performance of one of his string quartets.

Why Selection?

To reiterate: an archivist is usually the opposite of an individual who makes selections. By nature the archivist is striving for an ever-growing collection; including whatever he can get; excluding as little as possible. Why should he then apply selection to the collection of recordings ready to enter his vaults? There could be three possible reasons:

-

Lack of space

New technical developments will eventually allow smaller formats for records, yet space will always be an argument in favour of selection. Audio-records also demand certain standards of air-conditioning which may involve a considerable investment of money. -

Lack of staff and equipment for preservation

Preservation may consist only of keeping air-conditioning under control and a regular check on the stability of the records in storage. But old and deteriorating records have to be copied, involving time-consuming operations, sophisticated equipment and a quantity of blank carriers. -

Lack of staff for cataloguing

The accessibility of the recordings in our archives is of course very much dependent on the quality of the catalogues we are going to produce. Even a simple catalogue of audio recordings should be based upon standardized title descriptions. For example, the ISBD, while spoken word recordings demand an additional summary of the contents. The descriptions should be classified according to some system using keywords derived from an authority file such as the one produced by the Library of Congress. Cataloguing is, therefore, a time-consuming affair.

Selection should be seen as a means to diminish investments, exploitation costs and above all the considerable costs of staff necessary for preservation and cataloguing.

Criteria For Selection

The term selection implies a procedure based on the general policy of the archive and certain criteria within the limits of the policy. What criteria can we establish without hampering future research and destroying recordings which, in a hundred years or more, could have become interesting or even indispensable? Are there methods to avoid disaster and to protect ourselves from blame by our successors? It is doubtful whether such criteria can be found but we should try to formulate a few points which can be applied without too much risk. Apart from obvious things like the discarding of dubbings or recordings of very bad quality, the following should be taken into account when an archive begins to define selection criteria.

-

The specific qualities of the medium

Sound archives are collecting music and spoken recordings or are concentrating on one of the many other fields. Spoken word can, of course, also be preserved in writing or in print. It is, however, not really possible to convey on paper variations in tone, laughter, sighs, chuckles, interruptions and intervals-in short, non-verbal expressions. This does not mean that one has to preserve every recording of spoken word. We should restrict ourselves to records, which contain medium-specific information. So many recordings of speeches by official persons, made entirely in accordance with the policy of their government, are in fact second-rate sources which do not add significantly to the knowledge stored in traditional archives of written and printed records.All of this means that we should concentrate on recordings made without previous preparation such as live-interviews, discussions and improvised talks; in other words, recordings, which enrich already existing, printed reports in the daily papers and official documents.

Medium- specific qualities apply also to music recordings, since such recordings cannot be replaced by printed music in any way. Thus the first criterion will seldom apply to music, because it is by nature medium-specific and irreplaceable.

-

The division of work between archives

Most spoken word archives are in fact specialized institutions, concentrating on restricted fields, and usually there is only a small overlap with other institutions. If there is duplication, as is sometimes the case with broadcast sound archives and research archives outside the radio, it is there because radio archives are not able to provide a service outside their broadcasting institutions. However, the general policy of archives should be very clear about the limitations of their own collection as well as others and selection policy should take account of these limitations. This applies equally to spoken word and music.

-

The length and completeness of recordings

Selection has also to do with the length and completeness of recordings. This does not mean that only extensive and complete records are valuable, because a very short abstract from an early broadcast may be worth many long recordings of later date. In the case of spoken word it is particularly difficult to decide to what extent fragmentary recordings are useful. News broadcasts, for instance, which are transmitted by the dozen every day, usually consist of many comments and few authentic sounds. They are useless for research and for most educational applications. On the other hand complete recordings of live interviews belong to the more important part of every archives collection and must certainly not be eliminated because of a too strict selection policy. In the case of music, complete recordings are preferable in most cases.

The above-mentioned points give us something upon which to base a policy. In short: are our recordings adding to the traditional written media or are they worthwhile because of their specific qualities as sound records? Are they held elsewhere in the country or abroad, or are they too short and too fragmentary to provide useful information? Criteria along these lines will in general not impede any future research.

There are a few additional points, which are more risky, but can do little harm to our descendants in the world of sound archives.

4. Single records or complete collections

Most records, be they spoken word or music, belong to series or to collections brought together with a specific aim. In many cases records derive their importance from the mere fact that they belong to a collection, while single records without any relation to other recordings stand apart and may be less valuable. The recording of a well known Haydn Symphony by a certain orchestra under a particular director is of course different from the same symphony recorded as part of the complete series by Antal Dorati and the Philharmonia Hungarica.

5. The importance of the subject: estimation of value

Frequently spoken word recordings have been made because at the time people seemed to be interested in the subject. Radio broadcasts, in particular, tend to be of temporal value, fashionable or tied up with sudden bursts of sensational curiosity. Archivists should be able after some time to distinguish between temporal and more enduring subjects. There are risks in this approach, because any tape may contain the one and only recording which eventually proves to be of outstanding value but, as long as we deem selection to be necessary, the subject-criterion provides another weapon against pollution of our precious collections. Archivists of music recordings may easily find parallels within their field of interest.

6. The importance of the subject: social history

There is a tendency to apply social sciences and historical research to daily life, the life of the man in the street, the unemployed, workers in factories or minorities in great cities. Aside from the inevitable exaggeration of this movement, it is nowadays a matter of common understanding that historians and archivists have spent too much time on outstanding events and very important persons, and that they should change their course. While a lot of documents cover the dealings of the so-called establishment, the number of records related to the circumstances of living and the cultural interests of the public at large is relatively small. Selection should take care of this distinction and place less value on outstanding persons and more on social history, at the cost of our customary collections of voice portraits of VIP’s, who as a mater of fact are well prepared for eternal life anyway.

Further to this summary of the criteria of selection in general terms, it should be indicated that for each specific subject of research, whether music or one of the many fields of spoken word, the archivist may develop his own criteria within general parameters, dependent upon the policy of the archive and the point of view within that field research. However, it is not easy to use more specific criteria without grave risks of the wrong kind of perfectionism. General directives and a well-developed common sense are better remedies than so-called scientific criteria which, in practice, spoil much of the fun of collecting and do not really add to a well-balanced archive collection.

The Selection Process

Before moving on to the process of selection, a few preliminary explanations are required. It should be stressed that this paper has to do with spoken word, although it may also apply to music. Also, the figures used by way of explanation about the effectiveness of selection are based upon both experience and speculation. If they have any significance it is because they may stimulate the discussion and provide a kind of model for calculating. Lastly, the article is restricted to matters of personnel, not investments and costs in the material sphere, because the costs of equipment and materials are usually far less forbidding than the costs involved in hiring staff.

Finally the selection process has been related to the cataloguing. Records which have been selected for further use will, in any case, pass through the cataloguing process in order to become accessible. It is, however, doubtful if all of them will also go through a stage of copying and further preservation. After passing the selection process many recordings will indeed return to storage without further preservation. Including preservation in this calculation model would complicate things unnecessarily.

The selection process consists of a series of actions which lead to the decision to send the collection or the single record for further processing through the archive (positive selection), or to exclude it from further processing or even to destroy it (negative selection). Within that kind of process there are many possibilities, differing in degree of intensity relative to the needs of the archive and the kind of input of records in the archive. At one end of the scale we find coarse-mesh selection, and at the other end fine-mesh selection. Coarse-mesh selection is the evaluation of complete collections of recordings without going into each record specifically. Fine-mesh selection is based upon a record-for-record approach necessary, for instance, in case of probable copying, bad technical quality, etc.

In the first case the selection process is usually not very time consuming, which means that the ratio of the size of the collection and the time spent on selection is advantageous for the archive. However, coarse-mesh selection is risky whenever the collection is not already well defined and well documented. If this is not the case, one may end up with a lot of rubbish and a few really valuable recordings.

In considering fine-mesh selection it is worthwhile to go into the question of effectiveness of selection in more detail. The process of selection with a fine-mesh approach consists of several stages:

- Getting the record from storage;

- Inspecting the container, the sleeve, the label and the eventual documentation with the record;

- Listening to the complete record or to part of it, and/or studying an eventual detailed list of items of the recording;

- Filling in a selection-form with headings for a few primary dates;

- Sending the records back to storage;

- Evaluating the findings and taking a decision about positive or negative selection. Completing the selection form.

Stages 1 through 5 can be described as a pre-cataloguing process because, in the case of positive selection, the selection-form can, amongst other things, serve as a tool for cataloguing proper.

Selection of Different Records

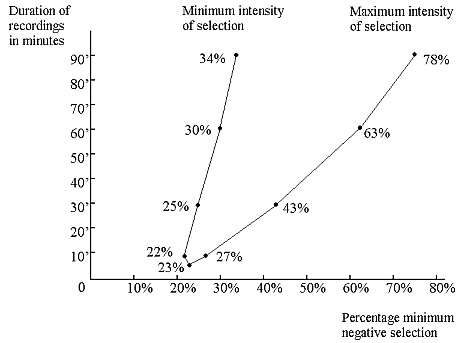

Let us compare a few imaginary records of ten-, thirty- and sixty-minutes duration by running them through the selection stages mentioned above and estimating the time taken for each stage. In doing this we can also make a distinction between a selection process in which the record is listened to completely, for instance in the case of dubious dubbings or a great many separate items (maximum intensity), and a process in which only part of the record is listened to (minimum intensity). See Table1.

|

Duration of recordings |

10m |

30m |

60m |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stages of the selection process | min. | max. | min. | max. | min. | max. |

| 1. from storage | 3m | 3m | 3m | 3m | 3m | 3m |

| 2. inspection | 5m | 5m | 5m | 5m | 5m | 5m |

| 3. listening | 5m | 10m | 10m | 30m | 20m | 60m |

| 4. filling in form | 5m | 5m | 5m | 5m | 5m | 5m |

| 5. to storage | 3m | 3m | 3m | 3m | 3m | 3m |

| 6. evaluation and completing from | 5m | 5m | 5m | 5m | 5m | 5m |

| Total of selection process | 26m | 31m | 31m | 51m | 41m | 81 |

Table1: stages and durations of two different selection processes for recordings of three different durations (in minutes)

It is not insignificant that the only variable figures in this table concern the time necessary for a minimum or maximum listening to the recording. All other figures are, generally speaking, the same for every kind of record. (The storage time has been limited to three minutes each because one should, of course, handle a group of records all in one.) There may be some differences between the one and the other single recording, but such variations are not significant for our comparison. It must be noted, however, that part of the pre-cataloguing process does not have to be repeated during the cataloguing process proper. We should, therefore, deduct some time from the total duration of the selection process in order to make a comparison with the cataloguing process more meaningful. But a suitable cataloguing process should include the listening stage, particularly in view of the production of a summary and the determination of keywords. Only a few data listed on the selection form might then serve to speed up the cataloguing process and you cannot subtract more than five minutes on the average from each of the total times mentioned in the table.

We may, in any, case safely conclude that

if selection does not result in the de-selection of a certain number of records, it will only add considerable additional loss of time to the existing lack of time of the staff.

The duration of the selection may very from twenty to eighty minutes or more per record, depending upon the duration of the recording and the amount of listening we decide to do.

The Cataloguing Process

In order to underline the point, let us take a close look at the cataloguing process and list the stages involved in the process with their estimated durations (a simplified reproduction of the total process). See Table 2.

|

Duration of recordings |

10m | 30m | 60m |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Stages of the cataloguing process |

|||

| 1. from storage | 3m | 3m | 3m |

| 2. standardized title description (the complete process) | 45m | 45m | 45m |

| 3. summary | 20m | 30m | 45m |

| 4. subject-code and keywords | 15m | 15m | 15m |

| 5. input in database | 10m | 10m | 10m |

| 6. to storage | 3m | 3m | 3m |

| Total of cataloguing process | 96m | 106m | 121m |

Table 2: Stages and duration of the cataloguing process for recordings of three different durations (in minutes).

Here also there is a relationship between the duration of the recording and the total duration of the process. The variable is in the summary stage which varies according to the duration of the recording because a longer recording will usually be more time consuming than a shorter one.

In comparison with the cataloguing process, selection takes a lot of time. If we put together the minimum selection figures table 1 and the cataloguing figures from table 2 and subtract five minutes from the pre-cataloguing phase, Table 3 applies.

|

Duration of recordings |

10m |

30m |

60m |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1. selection (minimum intensity) |

21m |

26m |

36m |

|

2. cataloguing |

96m |

106m |

121m |

|

Total time taken |

117m |

132m |

157m |

Table 3: duration of selection and cataloguing for recordings of three different durations (in minutes).

To make the comparison work for a group of records ready for a fine-mesh selection process followed by the cataloguing process, let us take a group of one hundred records with an average duration of 30m per recording (resulting in 26m for minimum selection and 106m for cataloguing). Consider that the records pass the selection with flying colours, so that all of them get catalogued in the end. The total duration of processing these records through selection (minimum intensity) and cataloguing would then amount to the following: see Table 4.

| Number of recordings | 100 |

| Average duration of recording | 30m |

| Selection (minimum intensity) | 43h 20m |

| Cataloguing | 176h 40m |

| Total time taken | 220 h |

Table 4: duration of the selection and cataloguing processes for 100 recordings of thirty minutes average duration (in hours).

One person, working effectively seven hours per day, would thus spend more than six days on selection and more than twenty-five days on cataloguing those hundred records.

In this case the selection process, seen from the point-of-view of the selecting archivist, was entirely without result. But when does selection become effective? In other words: where is the break-even figure at which it is to the advantage of the archive to process records through the selection procedure and above which selection is a waste of time, indeed only adding to the problems of the archive?

The Break-even Point

Take the following supposition:

As long as we succeed in keeping the total time involved in the selection and cataloguing of a certain number of records equal to the time which would have been used for cataloguing without previous selection, there is an advantage for the archive.

Even if we do not win time during the selection and cataloguing processes, we will have less to store and eventually less to preserve. And we are not losing any time by selecting carefully.

However, if we succeed in making the total time involved in selection and cataloguing less than the time originally involved in cataloguing proper without previous selection, then selection becomes even more advantageous. But as soon as selection and cataloguing time add up to a total higher than the cataloguing time without previous selection, we pass the break-even point in the wrong direction. Then the archivist should decide whether problems of space and preservation might counter-balance the loss in time on the selection/cataloguing side.

Now what does the break-even point mean in the case of our hundred records? Taking the figure of 176h 40m involved in the cataloguing of those records (again: 30m average duration, 106m cataloguing per record), if we are going to put those 100 records through the selection process and if we are only going to catalogue the records which were positively selected, we should nevertheless stay within the limit of those 176h 40m in order not to lose time. To find the break-even point in this case becomes a very easy procedure.

We have to go through the selection process anyway for all hundred records. As we have seen this process takes up 43h 20m (again: 30m average duration which means 26m selection per record). Now we only have to subtract those 43h 20m from the 176h 40m mentioned above to find the time which we can safely use for cataloguing proper.

Thus we have 133h 20m left for cataloguing. As long as we stick to 106 minutes per record for the cataloguing of each of these 100 records, we are then able to catalogue about 75 records without going beyond the break-even point. In other words:

There is a break-even point below which it is even more advantageous to select and above which the archive may lose extra time by selection. The break-even point can be found when one subtracts the time involved with the selection process from the total time, which would have been involved with cataloguing all records, in question if there had been no selection. The remaining time is left for cataloguing and should be divided by the time necessary for each separate record in order to find the total number of records, which can safely be considered for cataloguing.

An archivist should in this case instruct his staff to de-select at least one quarter of the pile of one hundred records in order to make the selection a useful tool in the process of saving staff time and money. This assumption is based upon a selection process with minimum intensity. More intensity means a deteriorating ratio, which may even go beyond fifty-fifty.

100 audio-recordings of different duration – fine-mesh selection with different intensity

|

Average duration of recordings |

10m |

30m |

60m |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity of selection | min. | max. | min. | max. | min. | max. |

| Total duration of cataloguing if no selection |

160h |

176h 40m |

201h 40m |

|||

| Total duration of selection minus pre-cataloguing phase | 35h | 43h 20m | 43h 20m | 76h 40m | 60h | 126h 40m |

| Total time available for cataloguing after selection | 125h | 133h 20m | 133h 20m | 100h | 141h 40m | 75h |

| Duration of cataloguing per record |

1hr 40m |

1hr 45m |

2h 1m |

|||

| Number( = percentage) of records to be selected for cataloguing | 78 | 73 | 75 | 57 | 70 | 37 |

| Number ( = percentage) of records to be de-selected | 22 | 27 | 25 | 43 | 30 | 63 |

Table 5: calculation of the minimum percentages of audio-recordings of different duration to be de-selected in a fine-mesh selection process of two different intensities, in order to prevent extra loss of time because of selection.

A greater percentage of de-selected records is more advantageous to the archive in terms of timesaving. A lesser percentage means greater loss of time and makes selection disadvantageous in terms of timesaving.

Table 6: minimum negative selection with recordings of different duration

Conclusion

The purpose of this exercise in sound archive arithmetic is, of course, not to deliver a ready-made calculation model for all kinds of selection. It is, at best, a clue to the solution for a small part of the total selection problem. Establishing reliable and effective criteria is probably a much more difficult problem to solve.

However, to get back to the beginning of the paper, it is important for any archive to establish the general policy with regard to the limits of its collection. Only when it is apparent that, even within those limits, the archive simply cannot cope with the amounts of records pouring in, it should consider a more energetic selection procedure. Even then, it is better to try a kind of coarse-mesh selection in order to lose as little time as possible on that stage of the total processing of records through the archive.

If, however, records enter the archive without any cohesion amongst themselves or without any connection with the collection already present, it is necessary to apply a fine-mesh selection. In this case, it is advisable to consider the ratio between the time necessary for selection and the time involved in further processing through the archive including the cataloguing process. A fine-mesh selection, which does not result in at least one quarter of the records being thrown out, can eventually end in a bad result in terms of costly hours. See table 6.

One final consideration. Negative selection does not always have to end with the destruction of the records. If space is no problem, one can, of course, store them in some part of the archive where they can do the least harm. One can also offer them to another archive. However, sometime it is definitely better to pull oneself together and have the records either thrown out or destroyed. If some archivists here or there still believes in miracles, the author is the last one to attempt to awaken them from their dreams. However, we can be very certain that the longer we wait, the less money will be available and the more our conscience will bother us. A well-established selection policy, consistently carried out, is the best solution.

Rolf Schuursma was the librarian of the Erasmus University, Rotterdam.

This paper was given at the IASA conference in Budapest in 1981.

Oral history criteria for selection in the field (David G Lance)

At risk of stating the obvious, let us begin with some general considerations that affect fieldwork decisions. Archives do not exist in a selection vacuum. There are three major factors, which dictate and predetermine what the character of their fieldwork programmes will be.

First, archives are established usually for quite specific functions that are defined by their founding authorities. Their activities are guided generally by the policies of the institutions they are a part of and the overriding criteria for their fieldwork activities should reflect the charters under which they have been constituted.