Annual Conference: Canberra, Australia (with ASRA)

President: Gerald D. Gibson, Library of Congress, United States

Editor: Grace Koch, Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies,Canberra, Australia

IASA Board Members

Presented at the Open Board Session at the IASA/ASRA Conference, Canberra, 1992.

INTRODUCTION (Gerald Gibson)

The title "Towards 2019, or IASA at 50" describes the purpose of this session. It is the outgrowth of many discussions by a number of the entire IASA membership over many years. For some of us it began to coalesce in Sopron with Ray Edmondson's keynote paper, which has been since published in Phonographic Bulletin No. 60, May, 1992. Ray's presentation and the discussion which followed acted as a catalyst for many exchanges during the Sopron conference. These culminated in the comments and the working meeting of the representatives of the various IASA affiliates- ASRA and ARSC and AFAS, for example, and the like, of the national organisations, of the committee officers and of the Board.

The general tone of that final working session in Sopron was where are audio and moving image archives going and what should our association do to be in a position to help sail that course. Following that meeting, three members of the IASA Board took on an assignment to pull together the essence of those Sopron discussions, to deliberate upon these questions, and to come to our midyear Board meeting ready to lead the discussion on this vital part of our itinerary. They did their job very well and their thoughts and suggestions were indispensable in our deliberations in Maastricht where we debated, sometimes fairly heatedly, exchanged ideas and views, and generally brainstormed the topic.

At Maastricht we agreed to bring a condensation of our thoughts to you in Canberra, and to ask for your views and ideas on the topic.

I shall present a perspective of where we on the Board anticipate AV archives will be in 2019— the year when IASA will be 50 years of age. Following this, brief summaries will be given by each of the Board members on one or another of the topics which we feel are of major concern and pose potential, if not major, problems. They will conclude with our vision on how these problems can best be addressed and resolved.

We will address the topics in alphabetical order: access, availability and user interaction, administration, political environment, legal and copyright, cataloguing, bibliographic control, development of the profession, training and certification, preservation, restoration, re-recording and storage, and selection, and acquisition. We will give summaries of our thoughts, and please bear in mind they are only our thoughts on these issues. Our presentations will be direct and, hopefully, succinct, and will aim to allow adequate time for group discussion.

I wrote to each of the committee chairs asking them if at all possible they could include some of their working session time for discussion on the topics most specifically pertinent to their committee and to include a summary of those thoughts and conclusions or need for further discussion, consideration, and debate, in their report to General Assembly II.

Finally, and most importantly, since we all know that all of our membership are not able to attend these conferences, please put your thoughts on these topics and any other which you feel should be included in this exercise onto paper, and send them to Grace. She will see that they are organised and included in a written summary of the discussions and presentation of this subject for dissemination. It's not necessary for you to have thoughts on all of the topics listed, but we hope you do. It is important, however, that you have specific points to make on at least one of the issues, since they concern every one of us.

hether you support or give differing views to those of the Board is immaterial since it is the breadth of our group perspective that is being sought. It is very important that you, as leaders in our profession prepare and share your thoughts and perspectives into our profession.

What then does your Board believe 2019 will have and be for AV archives? We see the coming period to be one of major change. We believe that the several efforts being made to provide on-demand world-wide access to all of the accumulated knowledge, including audio and moving image data- along with their supporting documents must merge into a coordinated, collaborative whole. This means that for the cost of relatively inexpensive equipment, comparable today to a laptop computer or less, and for connect time- possibly through a telephone or through some other communications means- virtually any person in the world will be able at any time of the day or night to see, hear, and study the various parts of any of our collections from the comfort and convenience of their chosen work site. No longer must they have what amounts to privileged knowledge of what is in a given collection and travel to that geographic site, and, for the limited hours that our collections are open for their use, sit and access the data that they wish to have.

We believe that coordinated conservation and preservation will be a reality. Since Archive A, if our above presumption holds true, can see and hear what Archive Β has, including the completeness of the copy, its quality, and its provenance, they can easily discern if the copy they have is unique or is more complete than those already available to the shared resources.

We believe that the wealth of information available through the best of today's technology, through the world's libraries and archives, through publishers, through broadcasting facilities- whatever those facilities may be today- will be so drastically overshadowed by the scope, depth, and technical quality of data that is available in this on-line demand basis— that the future will look back on our time- the late 20th and early 21st centuries- as being parallel to Europe in the 1430's and the 1440's- the period immediately prior to the introduction and acceptance of moveable type to Europe.

We are concerned that the "haves" and the "have-nots" of the world will be even more widely separated because of such massive dependence upon technology for producing, storing, accessing, and distributing its information. We believe, however, that the potential for such an abundance of information at so comparably inexpensive a price can reduce this gap and bring about greater acceptance and understanding of the differences and the similarities between the races and the cultures of the world.

Finally, we fear the potential for information control, modification, or distortion such is envisioned in George Orwell's 1984, and we fear it is very real. Yet we believe that the potential gains for society are such that means must be found to prevent such misuse and manipulation of information.

Assuming that you can accept even a small part of our forecast, and that you agree that the availability of such quantities of information is desirable, and will help to make this a better world in which to live, the questions are:

What then does IASA need to do to assure that archives are ready for this "brave new world," this challenge for the future?

What are the problems of our profession that would slow such an evolution? What do we, as the administrators of the collections which hold much of this data need to do to make sure that the information which we have helped to acquire, organise and preserve, is available in undistorted form to share with our fellow residents of the earth?

ACCESS AND AVAILABILITY, USER INTERACTION (Marit Grimstad)

An archive that is not accessible is not an archive but a storage house. I hope there are few archivists left in the world of the old type that collected for the sake of collecting and not with the hope that what we collect today would be of use for future generations.

There are two main types of access to an archive: long distance access that is on a national or an international level, and on- premises access in the archive or library. I do believe that the situation in 25 years time will be what Gerald just described to you with the possibility of worldwide access by telecommunications. Two strong points today in how to reach this goal are that much of the needed technology does already exist and that most archives today already are computerised.

Some weaker points in today's archiving world that will slow our progress in reaching our goal are:

The Board agreed that the unwillingness to share the collection is a weak point in today's archiving world; however, I don't think this is always so, and I will give you an example. In most European countries, broadcasting has been State protected and State run, and we have had no competition. Now the situation has drastically changed. We are thrown out into a very competitive world where we have to fight for our listeners. In this situation, the national broadcaster sees the archive as one of the main competitive assets. We have 50 years of radio history in the archives that the new radio stations are dying to get their hands on, so we don't want this open access. It is a strong point for certain archives.

In 25 years time I don't think we all will sit in our homes and access archives all over the world. We will still have the traditional user who comes to the archive to get help from an archivist or a librarian. His access to the archive depends a lot on the quality of the service he receives. We archivists and librarians, we always think we give very good service. We think we do our best; however, the Americans have something they call the 55% rule. Two Americans by the name of Hernon and McClure conducted a survey on quality control of reference services in libraries, and they found that 55% of the answers given by librarians were either completely wrong or very much lacking in information. A survey done in Danish libraries shows similar results, and I would say that if sound archives are no better than this, access is a very weak point.

Now to the problem solving. What can sound archivists do to change the situation? IASA can take topics such as copyright, long-distance data access, and standardisation of formats, to the Round Table and work together with other archival organisations to ensure standards for all. I think it is important that IASA doesn't go alone but works with other non-government organisations to ensure international standards.

IASA, of course, is not a body for developing technology, but I think IASA, especially through the technical group, can work to influence the manufacturers to develop the right technology for archival use.

The other weak points I mentioned about access, such as cataloguing standards and legal problems, will be addressed by other Board members. When it comes to user interaction and quality of the services rendered I think that IASA can do a lot as quality management and quality control of these types of services are a relatively new field and few standards for quality have yet been set down. It is therefore important that IASA get into this work so we can influence world standards.

POLITICAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE ENVIRONMENT (Giorgio Adamo)

I would like to present only some general remarks on a topic which has not been greatly considered in IASA's activity until now. I will speak on administration in very general terms, particularly in regards to political environment.

We should pay attention to the political and institutional status of sound archives, of audiovisual archives. Also, while we are considering the future of IASA, we should examine the future of archives as institutions. This examination must take into account the context in which we work and in which we live. In addition, the political and financial situation in many countries does not make our work easy. I know Italy is not the only country that has problems at this moment. In many situations we have to deal with cutting of financial support to cultural activities, to institutions, and so on. Furthermore, I think we should see what is happening outside our archival circles because this could become very important for our future.

Another problematic aspect is the cultural context concerning our activity. I mean, while we are here speaking to one another in our cultural context, we speak in terms which are obvious to us when we say that we are preserving an important part of the cultural heritage- that what we preserve has a deep human value. But I wonder if outside our professional world there is the same awareness of the value of what we are doing, of what we preserve. This is important because we see that around us everything is moving towards commercialisation, and there is the risk that we could be forced, or to some extent, to feel the pressure to move towards commercialisation. This could be one of the real problems in the future.

Our archives are independent of (or operate actually against) the logic of the market. We know for example that if the market could supply us with an infinite number of duplicate carriers, and if what we are preserving in our archives can also be easily found in a shop, the situation would be different. Therefore the maximum value of what we preserve in our archives is sometimes due to the fact that what we preserve is not available on the market. This is particularly true for archives within IASA, for example, national archives or research archives.

However, we should not forget that in many cases the important role of the archive is to produce documents, to produce unique recordings. We do not consider this aspect seriously enough; we are much more concerned with the problem of preservation. I would like to see some papers and discussion about producing documents and recordings in one of the future conferences. This could be also an important part of our role and an activity that could increase our status.

So, what can we do? I think that we should go outside our restricted archival world and find out all possible ways to increase the awareness of the importance of our institutions. I see that we can move in two directions. One is, of course, to address governments and international bodies and institutions. Here, probably, we have a strong point. We have our status in UNESCO, for example, and we could use this international status in trying to speak to our governments.

Secondly, we should address the users and potential users of our institutions. Perhaps we should look into activities like advertising or marketing. I was quite surprised to see here in the Canberra tourist guide a nice description of the National Film and Sound Archive as one of the places of interest for tourists. I was much more surprised in learning from Kurt Deggeller that, while he was flying to Rome, he found, in that kind of magazine you find in the plane, a half page devoted to the Discoteca di Stato, our institution in Italy. I have no idea who wrote that. I am curious to see! I wonder if this way of reaching people-- of circulating information— could help us to increase our role and status. Also in marketing, like for example, here in Canberra is a shop in the National Film and Sound Archive. I couldn't imagine something like this in my institution— selling t-shirts with Discoteca di Stato or something like this, but maybe we could consider such an activity. In summary, I believe it would be good if we could start to think a more about these problems which concern our role and status in our society.

LEGAL AND COPYRIGHT (Sven Allerstrand)

Twenty-five years is, indeed, a very long period of time and it's almost impossible to predict where technological development will bring our profession by then. My guess is that the different media— text, audio, and video— will continue to converge and it will be possible to reduce the storage space dramatically, which means that the costs will decrease. There will be automated systems for retrieval, access, preservation, and so on. These will give us the possibility of having more ambitious preservation programmes than we have today. This will be necessary, because the market for sound and images will definitely increase. In this perspective, I can see two major legal issues which have to be dealt with on an international basis.

The first is to include AV material in the legal deposit system that already exists in most countries for print material. I'm more optimistic than Giorgio on this point because I think that the importance of sound and moving images will be more obvious, and I am convinced that there will be a growing awareness of the fact that these media must be systematically preserved to the same extent as books and other printed publications.

Since the task is so enormous, it is essential to avoid duplication of work, both on a national and on an international level. Radio sound archives, national archives, and other specialised archives must work closely together with combined efforts instead of rivalry. The basis must be an international agreement where every country is responsible for the storage, preservation, and the documentation of its own productions.

An important task for the international AV archive organisations will be to produce a model legislation, perhaps with different levels, for AV material. I know that a lot of work has already been done in this field, in France and by UNESCO, for instance, and this provides a good basis. But we have to transform this work from suggestions and guidelines into recommendations which have been agreed upon within our association. Otherwise there is a risk that this legislation will just be an extension to the existing laws. The job will be done by lawyers, librarians, and or paper archivists with not enough attention being paid to the special characteristics of our media.

The other legal issue is to provide access and availability to our collections. Sound and moving images are internationally spread, as we all know. In Sweden we can listen to and watch records, films, and TV programmes from all over the world. And I was especially happy to see a Swedish film on television here in Canberra the other night. These records are an important part of our everyday life, and they have, of course, a big impact upon our society and culture. Therefore it is necessary that they should be easily available— the foreign material as well— everywhere for all who have a need for that. And I am one of those who feel that it should be considered a public right to get access to the audiovisual heritage; not only for research and educational purposes but also for everyone who can show a serious interest and a reasonable purpose for their use.

So, in my opinion, a condition for shared responsibility on an international level should be that the material could be easily available to all, not only in the country of origin. The technical means for advanced distribution of recorded sound already exists, as we have seen earlier this week. So the important legal issue for an international archive organisation in this context is to try to minimise the restrictions caused by copyright legislation and international conventions for a reasonable, non-commercial use of the material.

First, we have to look into the present situation. What can we legally do today? Who can get access, and under what circumstances? What kind of copies are we allowed to make? After that survey, we should try to formulate a common policy for how we, as AV archivists, would like to make our collections available. This policy could be used to influence legislative bodies in order to get special provisions for sound and AV archives, both international copyright laws and in international conventions.

This will certainly be a difficult and laborious task. We will have to fight with very powerful copyright organisations and I think it could only succeed by strong international cooperation with combined efforts for all AV material. And I certainly hope that IASA will play a leading role in that work.

CATALOGUING AND BIBLIOGRAPHIC CONTROL (Grace Koch)

As all of us speak, the same principles appear again and again. I will repeat a lot of what Marit has said and also, I believe, Sven, in the following section.

The strengths that we see in our present systems of cataloguing are:

The weaknesses of cataloguing as we see it in relation to IASA are:

Some of the steps that we propose for solving some of these weaknesses are first of all, to find out what exists in cataloguing and documentation rules, throughout the world. Next, we need to see where these rules agree and disagree and to go through and resolve the differences. Then we would need to present the results for review and finally, agree to have them accepted as the international standard.

We also suffer very much from the lack of international standardisation of ADP systems. Some people have come to Canberra with diskettes and have found it difficult to get printouts.

We also need standardisation of names, subjects, and titles, and finally, there should be a shared possibility for cataloguing all media to avoid duplication. After all this work is done, we need a set of procedures to exchange data.

IASA could speed up this process of communication by funding and by establishing firm contacts for communication. A proposal for the implementation of such a communication project could hopefully go to the next Round Table.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE PROFESSION, TRAINING, AND CERTIFICATION (Magdalena Csève)

Information requirements have multiplied in a short time and the need for documentation is greater than ever. No matter where they work, archivists now face a far more demanding and complex task than ever before. While modern technology offers a more efficient means of storing and retrieving, it is certain to pose problems that touch the very core of the archivists' occupation.

We cannot avoid facing up to the consequences of the new ways people treat information. The question of identity and self-understanding is more vital than ever for archivists, both individually and collectively.

The intellectual development and training of the archivist needs to include the development of a conscious attitude of ongoing scientific research. This is urgent because the fields that are essential to us are developing so quickly that we must make a conscious effort not to lose the scientific basis of keeping archival material valid for society now and in the future.

There are many criteria for being admitted to our occupation. Some demand a distinct special education; others demand no skill in or knowledge of archival work but they do require an academic education, mainly, in history. Accordingly, we appear to have various conditions for admission to our occupation, diverse approaches to the ethos of archival theory, contrasting assumptions about the purpose of our assignment, and lack of agreement about what the main fields of archival research are.

These differences have consequences for forging our identity as archivists, and it is, of course, impossible to give one clear answer to the question, "What is the identity of the archivist of today?" The question we may pose is, "What is the identity we need to obtain in order to remain faithful to the archives of the information age?"

Sociologists have analysed occupations and professions by isolating the specific criteria that make an occupation a true profession. The characterisation of a profession has several aspects. A true profession covers an area which is important to society. Its work is, so to speak, institutionally-institutionalised altruism. Society gives sanction and recognition to a profession, because a profession takes care of important tasks on its behalf. The true profession is also given autonomy needed to do its task. It makes its own priorities and assessments and doesn't allow others in its field of competence. It defines needs on behalf of the individuals or group it serves.

Every profession possesses a body of scientific knowledge and a comprehensive specialised education to transmit this body of knowledge to aspirants. This education should be the only road to the profession, and those who undergo it must have the motivation to become members of the profession. Each profession forms associations to promote common goals. The profession, through its collective efforts, controls its own standards, such as for education and certification, terminology, ethos, ethics. A true profession has a common culture of shared norms, values, and language. This can exist only if the members of the profession have a common comprehension of the nature of their work.

As you see, it is more relevant to put the question, "How far we have come in the process of professionalism, in proclaiming us as a profession or as a non-profession?"

Our being professionals and our striving for a higher degree of professionalism— are undoubtedly beneficial not only to the archivist. This analysis is general and may be used in relation to any occupation. The aim is not to prove or to disprove that we form a profession but to see if certain features must be developed in order to strengthen our sense of being equal to the task which we perform for society. Thus we search for ways to develop archival theory, methodology, and practice for our time by building on and giving continuity to the principles and theory we already possess in order to meet the changes which come up so rapidly in the information age.

Undoubtedly we fulfil those criteria of a profession that involve the concepts of importance to society and sanction from society. We also possesses a certain degree of autonomy. Our autonomy is, however, still far more weak, sorry to say, and limited than it should be, if we are to pursue our task, namely to maintain an archive that communicates to and exists on behalf of society. This will happen only if we continue to strive for the authority and the resources needed to carry out our work.

The criteria of science and association are linked with education and standards and are the means by which we advance our work. Through education and association we create competence and self- confidence-- both of which enable society to understand us as a well-qualified group to undertake our responsibility and our tasks. Opportunities for the education of archivists are still weak in many parts of the world, even in the well-developed world, too. The lack of good educational possibilities is the Achilles' heel of the profession.

It takes a great deal of education to build strength and character into a profession. Archivists need the strength, character and integrity which is equal to the integrity of their archives.

Today the theoretical basis of education must aim to explain and define the special problems archivists face in order to keep and protect the archives of our society. If we promote and strengthen archival science and develop a relevant education for our occupation, we will prepare archivists to carry out a task that has been laid on them. Our ability to associate- to reach common goals, like knowledge and education, is only an instrument of professionalism, not its essence. Such associations are formed by archivists all over the world. Associations facilitate the communication and interchange of ideas by publishing professional literature, arranging professional fora on many levels, from working groups to seminars and congresses.

It is obvious that IASA offers the most adequate facilities to develop the proper method of defining the occupation as a profession. Special courses, seminars- both before and after the conferences- can offer valuable help for this defining of the profession.

The need for common standards is strong in several fields. Technical standards, for example, are necessary to describe archives' holdings and to communicate knowledge of them at a time when we may capitalise on the tremendous power of technology to store and transmit complex information. Education is another field where the profession itself has to set the standards. It's of crucial importance that the framework of education is defined by archivists to ensure the highest possible standards of qualification and conduct.

Active associations warrant the quality and force of our work. They are an incentive to cooperation and professional development and contribute to a common professional culture, shared norms, values, terminology, ethos, and ethics. This common culture is the final criteria of our profession. Such a common culture presupposes a common understanding of our duties and is therefore both an instrument for and a result of our professionalisation.

SELECTION AND ACQUISITION (Helen Harrison)

You might wonder why this topic has been included in such a forward looking session, for selection is such a currently essential part of our work. It is a working principle of any archivist rather than the policy of an association. Every archivist, let alone an audiovisual archivist, has a responsibility to organise, maintain, and make available the material within his/ her care. Selection, therefore, is a central activity in the organisation of the collection. It is also closely related to acquisition. It is also a precursor to many of the activities we have been considering so far. In order to maintain and to use a collection, you have to form that collection; that is, you have got to acquire and select material for it.

Selection is a pivotal activity. Selection and acquisition policies produce a collection. To avoid a waste of resources on cataloguing, retrieval, preservation, and exploitation— that is, the making available for use of the material- we need stated principles and policies for selective acquisition.

Acquisition: We need to know what exists already often in several locations. Some collections have less problems than others, that is, in- house collections such as exemplified by the Radio Sound Archives or many Oral History Collections which are based on recordings made in the archive or radio station. Their collections are likely to be unique, not available elsewhere and worthy of preservation by the institution in which they are deposited.

Selection: A greater exchange of information on selection principles, both nationally and internationally, is required, and this is something in which IASA should become involved through contributions towards directories of members' holdings and the design and establishment of selection principles.

As I see it at present, there are few examples available of acquisition and selection policies. People are re-inventing the wheel rather than being able to rely on suitable, accessible advice. If more selection policies, guidelines, principles were issued in published or unpublished forms, people would be in a better position to sift the information and select suitable policies for their own situation— they would not have to start from scratch, although they may well wish to amend and adapt principles to the particular situation and not wish to use another archive's policy in its entirety. There is an evident lack of standards or guidelines for all types of collection, both regional, national, subject-based, and so on. People seeking advice when forming a collection or trying to establish policies frequently have to resort to trying someone they know- that is, individual consultation, or picking a name at random in the hope that they come up with the right one.

IASA should, really, be surveying its members and gathering information into a central data bank or clearing house for information regarding these policies and practices of selection and acquisition.

IASA should also be developing discussion on establishing standards of good practice. Although IASA has been involved in discussions concerning selection throughout its existence, this has to be a continuing process. In the early 1980's, for instance, the Association held a series of conference sessions devted to the Selection process, and these were collected into one publication (ed. Helen P. Harrison, Selection in Sound Archives, 1984, IASA. NOTE: See list of IASA publications at the end of this issue for how to order.)

IASA was also commissioned by UNESCO to produce a publication on the archival appraisal of sound recordings. (Harrison, Helen P. The archival appraisal of sound recordings: a RAMP study with guidelines. PGI-84/WS/12. UNESCO, Paris, 1987).

Both of these publications are useful additions to the literature, but they are only a beginning, and we would like to encourage many more discussions, conference sessions, and publications relating to selection and acquisition— or, indeed, any other aspect of our work. By the year 2019, which is the year we are talking about- the 50th anniversary of IASA- the professional Association should have produced a substantial bibliography and boast an up-to-date, lengthy publications list detailing all aspects of our work.

But concerning selection and acquisition, I would look to the increased exchange of information on:

The Directory of Member Archives, for instance, should be published regularly with details of the scope of our collections, the content, the access principles, and so on. This is an essential tool for all member archives to locate unique information and also to decide what to keep in your own collection as opposed to what appears to be widely collected elsewhere.

Incidentally, may I mention that a World Directory of Moving Image and Recorded Sound Archives is under commission from UNESCO and they are expecting publication in late 1992 or early 1993.

Lists of holdings would be useful additions to the literature. These may be on the newer information technology providing on-line access or CD ROM access.

Such items would enable members to see what is being collected and where. It would also enable new collections to see where their own strengths and weaknesses are- whether a gap needs filling or whether one can rely on other collections elsewhere. Incidentally, I am not suggesting that we should all have unique collections. That is a very dangerous policy in the face of flood, fire, or unnatural hazards of warfare and even political warfare, which may deny access to unique material. We also cannot trust that an institution with a unique collection is in the position to maintain the material in usable and accessible format for future generations. But a greater awareness of what exists and where it exists would enable archivists to make educated decisions about what is useful to collect and preserve in their own collections, based on the knowledge of what already exists and the circumstances of collection.

Perhaps the formulation of these publications would be suitable cases for research grants for IASA.

This session is looking towards 2019 when most of us will be suffering from death or decrepitude. Let us hope our collections are not in the same parlous state!

But it is our responsibility now to set up good practices for selection and acquisition to ensure a spread of responsibility internationally so that we can all contribute to the conservation of the cultural heritage.

I think every archivist accepts the principle of selection, or, at least, I hope they do. Otherwise they may not call themselves archivists, rather, collectors or squirrels, and the latter are apt to lose their collections.

Without selection, 2019 will see an enormous, amorphous mass of useless and possibly inaccessible information—, and I would sympathise with the people of 2019. I hope that IASA will be able to develop principles and encourage the exchange of information to prevent such problems.

PRESERVATION, TECHNICAL STORAGE AND HANDLING (Gerald Gibson)

I believe the strengths and plusses that IASA has, to date are within IASA, because of almost 25 years of cooperation and working together to share information and to build information.

In the technical field, in particular, I believe one of the negatives is the lack of a centralised distribution or access point for technical data and information. Those of us on the Technical Committee, heard George Boston describe how the centralisation within the BBC has in many cases, resulted in the dissipation of technical support and data. Within our own association, we have the Technical Committee and we have our colleagues we can call upon, but we need to have its findings disseminated. We need to have it published, and we need to be able to do it in a shared and distributed manner.

I believe there is a lack of a generally accepted, if not a formally adopted, policy of preservation and restoration. I believe that there is a lack of accepted procedures and techniques which produce results. Many of us do our own thing and, unfortunately too late, we may find that we have done the wrong thing.

I believe we need a better understanding of the scope of the problems- the quantities we are dealing with, the difficulties we are facing. I believe we have a lack of accepted information in standardisation of digital sampling rates, for example, once again going back to the techniques.

I believe that some of the solutions in the technical area will come with the creation of a cooperative publication or data gathering and distribution programme, not only within IASA but with our sister associations. One of the discussions, for example, with the Technical Committee this week was with Henning to find out and to learn of his experiences in creating the FIAF manual, and some of the plusses and minuses that he has experienced with it. I believe we need the creation of a standing source of a clearing house. If at all possible, this should be a funded source. If it is not possible for a funded source, I fear that it will not take place.

I believe something that is essential in all aspects is training sessions. These should be developed and carried out in conjunction with the Training Committee of the Association and with our sister Associations. I believe that we can build upon them, once again, using FIAF as an example, with their very useful and very successful summer schools. I believe also one of the things we can do in those training sessions is to have concentrated, specific, directed pre- and post-session seminars at each of our conferences.

In general, in the environmental storage and packaging area, I believe the plusses are, once again, the cumulated knowledge that we have acquired through time and experience. However, I believe that the minuses far outweigh that information. We have conflicting information on the optimum storage environment and the optimum storage container for a given medium. We lack reliable information on packaging and its effect in life expectancy of the media and of the information which it contains.

Some of the possible solutions for these problems are independent study and recommendation of packaging, of environment, of techniques of storage and of handling. These should not be based upon our preconceived ideas and thoughts, because "this is the way I've always done it." Also, these solutions should be removed, if possible, from the needs of our industry colleagues to sell more products, and to convince us that the package they are selling us will last forever.

I believe we need the creation of and access to a catalogue of information to help us determine the technical needs— how best to apply the technical resources and technology we have on a timely basis and also to avoid the inevitable duplication of effort resulting from the lack of communication and lack of centralisation of our data.

(Editor's Note: After the presentations, there was discussion. The following summarises the points arising, identifying each speaker.)

Gerald Gibson: Magdalena, concerning the question of professionalism, do you feel that certification should be one of the things we attempt to develop and to strive for, and if so, do you have any thoughts on how it could be done, and if not, why not?

Magdalena Csève: I feel that some sort of certification should be required for the archivist. We could create it within the work of the association. And we have just mentioned the possibility of organising either before or after the conferences special training courses that would create professional archivists. IASA could organise these courses and offer some formal certification or diploma to those persons who took part on those courses.

John Spence: In Sydney, at the University of New South Wales, we have the only Archives Diploma course in the Southern Hemisphere. However, in this course, there has been very little attention given to non-traditional archives. The students pay a visit to the ABC and other non-traditional databased archives, but I wonder whether there is a role for IASA and the IASA Board in communicating with those tertiary institutions that do have courses on archives to actually broaden their perspective beyond that paper-based tradition.

Helen Harrison: IASA has taken part in the curriculum development report of UNESCO and you may have seen the report. This was something which arose from the Round Table— the Audiovisual Round Table which is part of UNESCO, and people like ICA, FIAF, FIAT, IASA and IFLA took part in a small working party to try to develop a curriculum for the audiovisual archivist generally. The report develops a one year course, basically, or a two year course, which is quite a commitment for any archivist to have to make while they're working. We did investigate the shorter courses as well through a world survey of all the existing institutions that were offering archive courses as such and also audiovisual courses or non- print archive courses, if you like. Now there were not very many, and very very few who are active in producing non-book archive courses.

There were several expressions of interest. We suggested that perhaps we could latch on to these existing institutions rather than reinvent our own institution, which would have been very difficult. And they all said, "Yes, what a good idea, but how do we find the time to include your interests as well as ours within that?" But it was a start, and I'm hoping that they will actually regenerate that particular working party in the short term.

John Spence: Perhaps the Open University could do something about a course.

Helen Harrison: Perhaps we could and perhaps we should. We have mooted this. We have also mooted the possibility of preparing distance education packages but it's very difficult to get something quite as radical as that through the Open University. More difficult than you would expect.

George Brock- Nannestad: I would put the blame for not letting the IASA membership know very much in depth about this study entirely on IASA and on the organisation of IASA. And this also goes for several for the UNESCO funded projects about which much too little has been distributed although there is IASA participation in it, and I think it is a disgrace. It was said at the Oxford Conference {Ed: in 1990) that this report was now ready. This is just an example of the lack of communication inside IASA and I think that is wrong. One sign of professionalism is that you have your inside communication in order.

Henning Schou: Just to share my experience within FIAF. There are three activities I am aware of. Over the last twenty years we have conducted the FIAF summer school in East Berlin-- done first in 1973 I think. And in June-July this year we conducted a very comprehensive three week training course in the National Film Archive in London which had twenty-eight participants from all over the world and also four from our own organisation which was a great success. And we are going to continue that.

It is quite expensive. It actually ended up costing us in the area of £15,000 to conduct. We had a language problem as well. We hope to solve some of these problems by holding a course, perhaps, in a French speaking country.

In Britain you can obtain a Master of Arts degree in archiving. It's conducted at the East Anglia Film Archive in collaboration with the National Film Archive. The first year, I believe, is mainly in film history and the second year is archiving course in collaboration with the National Film Archive. The course is two years old.

Also, I've just been approached about a programme, I believe, from Berlin. We have been asked about taking on a student who is looking at the re-recording of movie sound tracks. These are the activities I am aware of in the film area.

Ray Edmondson: Just to follow up the same point as Magdalena's contribution. It's one thing to seek to have courses of various kinds, and there is the summer school idea— the idea of seminars before and after IASA, and even the possibility of an AV component in library or archive courses. And all of those are important if we can encourage them, although they tend to make us appear that we are subservient to some other field, and so I think perhaps we need to go in a different direction.

I think it is open to IASA, FIAF and FIAT and to other associations to offer some certification or registration or call it what you will that recognises that an individual has the skills or the knowledge or the other attributes that merit that recognition, and that can be the professional standard in and how it is applied and how it can be given credibility. But the possibility of training- at least, of formal training, does not exist for many members of IASA or FIAF or other associations. Most people learn on the job one way or another and yet can be just as skilled as to what they do as the people who have had some formal training course, so I think it is over to IASA to perhaps consider how some set of registration could be introduced. I suggest this in consultation with the other associations. It can run alongside any training courses that are offered in various countries, but when the definition of our profession is finally set, it must be the associations that define the courses. So that would mean IASA would, in some way, define what their standards are.

Kurt Deggeller: I would like to speak on a more general point. Last year the Swiss government asked the different archives in Switzerland to develop a concept of AV archiving medias in the country, and we worked very hard for a year together- the National Libraries, the National Archives, Broadcasting Company, and also the National Sound Archive. And we made a very nice report- 50 or 60 pages— and calculated that we need investments of about 40 million Swiss francs- corresponding to about 40 million Australian dollars and about 8 to 9 million a year thereafter. We wrote to the relevant Minister, and he, "Oh yes, this is very nice report for now. You have to convince the politicians and also the public of the necessity to spend this money."

And here I recognised that this was the most difficult part of the job we have to do. We are not at all prepared to do that. That means that here at IASA conferences we try to convince each other that what we do is necessary, but as we are paid for that, it is very easy to convince us that we must be. But when we are to prove the necessity of what we are doing, and when we must define our public-- who are our users or our potential users- then our work becomes much harder. And I fear that we come more and more into the situation where other people do not see that archiving is an obvious activity. We believe that an archive must exist in any case and nobody asks why it exists. But then we have to prove that we have users and that the money which is spent for our archives is spent well.

I think we have to redefine our situation in society to some extent and also to collaborate much more with our potential partners- not only the broadcasters and the recording industry, but also the copyright societies for they are both active in the same field and we have to rationalise our work. We have to find efficient ways of collaboration with them if we want to survive and if we want there still to be AV archives in 2019.

Gerald Gibson: One of the points which the Board discussed at length at Maastricht was that many of us feel the lack of administrative skills and experience, such as how to prepare and to defend a budget. It might be useful if one of the seminars which were offered to our membership could be a several days seminar for administrators and supervisors, or for similar types of things that you are addressing.

John Spence: My comment is related to the operation of IASA. I have been talking to some of my colleagues here about how the committees seem to work in isolation from each other. I was wondering if the Board, like myself, and some of the people I've spoken to, see the value in joint working sessions of the committees for future conferences. Speaking from the Radio Archives point of view, the other committees touch very much on the work that involves us, and that goes for the National Archives Committee, also copyright and cataloguing. One or two joint working sessions in different committees would be very valuable.

Gerald Gibson: As you heard on several occasions, when talking about technical issues, cataloguing, or legality clearly play a part when talking about access, etc. We clearly feel that joint working sessions are needed.

You implied a question about the working procedure— the sessions and the programme in general. The working committees propose topics for open sessions and in general, develop their own agenda, schedule, and work needs. The Board can encourage or ask them to consider particular topics or areas, but the particular structure of IASA states that the committees are developed within themselves— they are developed with the agreement and support of the Board, but the officers are selected by the committee members— not appointed. The officers serve at the will of the members of the committee. The Board urges each committee to have elections- to choose officers, at least a chair and preferably a chair and secretary— at least once every three years. But there is nothing in the current structure of IASA making it mandatory for the committees to function save that they report on an annual basis to the General Assembly.

John Spence: I was really talking about how two committees and delegates who would attend those working sessions could work together on specific issues that relate to both committees- those who are interested in the work of those committees.

Gerald Gibson: It is the committee's responsibility to instigate it with another committee, in essence.

Grace Koch: There are open sessions of the committees that are open to observers- to people who want to contribute. I guess I would encourage all of you to attend whatever committee meetings that are open committee meetings that you can, because we need this cross-fertilization. It's a good point that you brought up, John. I simply want to encourage people to come and to contribute to committees.

Gerald Gibson: The Technical Committee has referred a couple of projects that it has been considering to the National Archives Committee and the NAC has set itself a task that directly interfaces with the Technical Committee. Possibly the Board should be more assertive, but it is primarily the initiative of the committees to do what you are describing.

Sven Allerstrand: I just agree, and I can see the point from the National Archives Committee and the Radio Sound Archives Committee because we- the two committees-deal with all aspects of sound archives- copyright, cataloguing, and technical aspects. So I would, along with the other two speakers— encourage cooperation between what we could call the professional committees and the function based committees.

Mary Miliano: It's been my observation over the years that institutions often say, "Wouldn't it be good if we shared our data and were compatible with each other and had the same standards?" and that, in fact, archives invariably do their own thing until they have a need to share their data. For instance if two sound archives find that they hold the same sort of material, perhaps through legal deposit in one archive and broadcast material in another, and they are in the same country, they suddenly say, "Yes, let's try to capitalise on having a compatible system." I feel that it's not until archives have a commitment or a need to share their data that we would actually succeed in having standard cataloguing rules across the board and sharing of data. I personally feel sad that archives don't have this as a high priority, but I realise they have a lot of other priorities that they need to attend to as well.

Gerald Gibson: I believe we have the need clearly. I believe one of the things that has been lacking is the means to share the data and clearly, with automation, the priority for cataloguing. Hence, automation has been concentrated on book and book-like materials, primarily, books themselves. Of the nearly one hundred million items in the Library of Congress, thirty-five to forty million non-book items are not catalogued. However, there is a major push for cataloguing staff to work on non-book materials. If your institution receives the MARC tapes, you will see that the quantity of cataloguing of AV materials has risen substantially. The major problem has been the lack of the technical capability to interchange and to access data- the problem of an ADP standard.

Ann Baylis: I wanted to mention that after a number of years of collaboration, the FIAF Cataloguing Commission has, this year, published the rules for cataloguing archival films. They saw the need for a standard across-the-board for all archives, and this standard is being used in South America. I am aware that there is a Spanish edition out already, as well as one in German and, possibly, French.

Gerald Gibson: Please let the Board know if you found this session to be useful. Please send any written comments and we will do our utmost to see that they are pulled together and distributed in a timely fashion. These ideas will help to form the Board direction in the future.

(Editor's Note: After the Canberra conference, several letters and articles have come to me in response to the Board Open Session, The following section consists of these responses.)

RESPONSES TO THE BOARD OPEN SESSION

Martin Elste

When I joined IASA back in 1976-77, I was seeking a group that assembled professionals in the field of classical music recordings. As a trained musicologist, I did not find such a group within the musicological circles. I did not mind that IASA catered for all other aspects besides the musicological one, and I even became interested in those other aspects. The combined conferences with IAML took special care for the musicological approach to sound recordings; I only recall the appropriate sessions in Mainz and Salzburg.

In the meantime, IASA has moved away from this area. Now its concentration focusses on the sound carriers as such and not so much on the content stored on those carriers. Certainly this has to do with the speed at which modem media formats change. Sound archivists have to be aware of these changes, and, furthermore, they have to be critical-- not an easy task.

But I, personally, would be more than happy to see some of the musicological aspects back within the IASA frame, and I think the (occasional) cooperation with IAML is not a bad strategy for that. It enriches the intellectual discussion within IASA and makes the association interesting for others professionals, too.

Were IASA to become an association restricted to professional sound archivists (whatever that might mean), I promise a decline in professionalism. There would be no Phonographic Bulletin, there would only be conferences made up of public relations presentations by the member archives. I happen to belong to such an "elite" organisation because I am not only a sound archivist in its strictest sense. It is good to see my colleagues of that association at annual meetings, but the outcome is restricted to a verbal exchange. Do we really want this?

Look at the Phonographic Bulletin.. A large section of each issue has, for years, been contributed to by individual members. Professionals usually are too busy with administrative and practical matters in order to write essays for publication outside their own institutions. Some of the most thorough book reviews in the Phonographic Bulletin have come from individuals, in fact, not even necessarily from members. We all profit from them. And, on this occasion, had IASA restricted itself to institutional members only, I surely would not have been able to develop the Reviews and Recent Publications section to its present standard.

Individuals are the real supporters of IASA- they stick to it and they believe in it. In the course of my fifteen years of membership, how many professionals have I seen come and go! George Brock- Nannestad, one of the association's most vivid professional non¬professional (i.e. individual) members, has suggested to change the association's name to "International Association for Sound Archivism." I think this suggestion is a very thoughtful as well as useful one. By working in a museum that is devoted to the many facets of music, and thus being confronted with physical objects of many diverse kinds— musical instruments, accessories, photographic objects (slides, negatives, ektachromes, prints), paintings and drawings, books, manuscripts, files, piano rolls, pinned barrels, films, and last but not least almost all formats of sound recordings, I know of the various needs archivists have in respect to all this material they have to care for.

On the other hand, I am quite aware that a global approach takes away a lot of thinking about the contents of these materials. I have experienced this phenomenon with the advent of electronic data processing. The time of writing or typing index cards gave, arguably, more time for thinking about the contents of what one was writing! And I fear that if IASA opens itself more and more towards all kinds of archival objects, it quickly comes to a point when that what is said about the scope of the association's prime interest can also be applied to collecting and storing potatoes.

A solution to opening the association to other media and, at the same time, to intensify the aspects of contents might be the cooperation with other professional groups such as the International Council of Museums (ICOM), and in particular with the CIMCIM and AVICOM committees of this huge association, as well as the cooperation with musicological societies, such as the American Musicological Society, International Musicological Society, and Gesellschaft für Musikforschung. Of course, we should not forget IASA's original base, IAML. But cooperation is only feasible if IASA can contribute to aspects that are of common interest. And here is the challenge for our journal, the Phonographic Bulletin. It should cater for a wider range of subjects about sound, and in order to achieve this, IASA will always need writers from outside its archival membership. I very much favour the introduction of special working groups, ie. an AV working group. But each of these groups should have a specific project to tackle. This will keep IASA alive and healthy.

REFORM OF IASA, SOME REFLECTIONS

Rainer Hubert

Let me start with something minor— the names of our committees.

I think it would be far clearer to differentiate between bodies dealing with different types of institutions and bodies dealing with different kinds of subjects. This would mean:

1. By institutions

2. By subjects

To strengthen this linkage I would suggest:

2.1 The NAOC chair should be a Board member in their own right.

Presently the chair is also a Board member but this is not stipulated by the Constitution. I think that we could reduce the number of elected Board members by one vice- presidency. The elected chairperson of NAOC should automatically become the third vice-president of IASA. Such a move would stress the importance of the national organisations, and such changes should be reflected in the Constitution.

2.2 The difference between the national branches and the affiliated organisations should be discussed anew.

Perhaps we do not have to differentiate between them. This problem is a difficult one and financial questions have to be discussed, but, because the present solution does not function very well, something has to be done. So why not come up with a "big solution?"

2.3 A re-shaping of NAOC could also further coordination on the AV-media field as such.

In the future, NAOC, not only national and regional organisations should be represented, but all professional AV- organisations, that is, FIAF and FIAT also! If an organisation the size of ARSC is an affiliated organisation of IASA (and we of them) why not the same with FIAT and FIAF? It would be worth trying. All AV- media organisations would be linked by this and the future NAOC would be the platform of all relevant bodies of our profession. It would be a first step towards achieving a unification without ruining the individuality of each of its parts. We would grow into one another. Just to cooperate is not enough, I think. A network has to be made.

2.4 There needs to be internal reform of the NAOC

One problem is that the national representative position is a job without prestige and clarity; up to now this was a job without any real work, just one little report per year. In the future, the representatives should be challenged much more. In some of the branches/organisations, the representative to the NAOC is chosen on the spot. I think this is a real mistake because there should be continuity. Could we ask all of the branches to nominate representatives and then to publish them all in the Information Bulletin ? If the Board or if some member wants to ask or suggest something to a branch/organisation, he/she can do so by contacting the representative. In some cases this representative may be identical with the chairperson or the secretary of the branch/organisation; in others, it may be another person. That is not so important. In my view, the main thing is that we all know who the link person is between IASA and a particular branch/organisation. The NAOC meeting itself should be dedicated to discussions of current affairs rather than a recital of lengthy reports on the activities of the member organisations, such reports should be given in printed form.

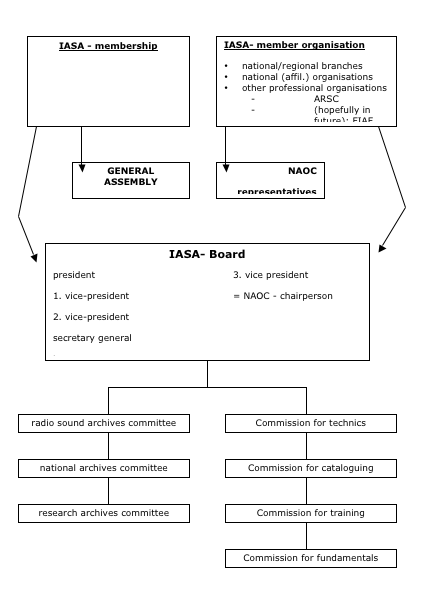

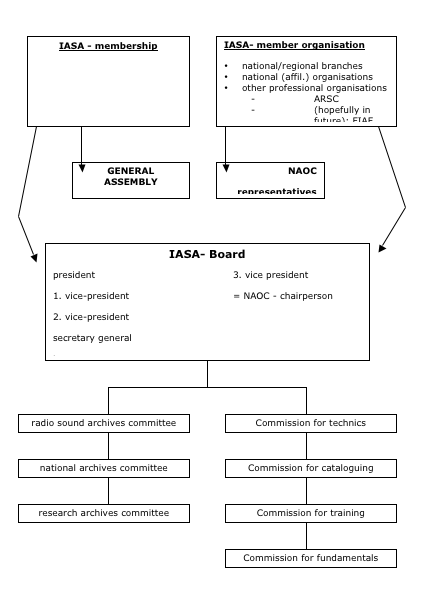

I propose the following schema for the interaction of the various contacts of IASA:

COMMENTS ON THE FUTURE OF IASA SESSION

George Brock- Nannestad

First of all, I would like to emphasise how relieved I am that the membership is not forced to make a decision before it has been made ware of the need for a serious debate. In particular I am happy that during the General Assembly in Canberra it became superfluous to vote on the proposed changes to the constitution as a packet-- this would have artificially created a confrontation where logic would have won, but where we would have ended up with a split association.

The non-controversial parts of the constitutional amendments were decided, but the major proposed changes still stand, and so we are still left with problems of terminology and with trying to understand the need for the change.

We live in a world where technological development may diminish the importance of actors in a particular field. This was the case for silent movie stars with the advent of sound movies, and it is the case of persons concerned with sound— audio— in the face of video and other visual media. One need only compare the investments in video productions to those of sound productions. The relative importance of sound is diminishing and so is- let us face it- - the relative importance of sound archivists.

But what is IASA? On one level it is a number of individuals who have a common interest because they work in similar environments. On the other level it is an international body, a non-governmental organisation which expresses opinions endorsed by a majority of its individual members. On a third level it is a platform for the officers of IASA: if the outside world perceives the organisation as being important, then the officers themselves are important.

What are the fundamental reasons for wanting to encompass "and audio-visual" as well as "sound" for which IASA was created? One model builds on the development of a number of archives: these archives experience a greater proportion of AV material coming in, and it is claimed that they do not know how to handle it properly. They are already members of IASA, and so they would be happy if IASA could help them.

Another model is that of making IASA a more important player on the international scene, because we would cater for a greater number of archives. Organisations presumably have to compete for the attention of the few archives world-wide. Another way to express this is that if IASA does not move, other organisations would step in or new organisations would crop up. All in all it is felt that the importance of IASA would diminish if IASA did not take the situation in hand.

Do we want to solve the problems of archives or do we want to solve the problem of the diminishing importance of IASA? This is the real test of the need to expand the scope.

In the absolute sense, taking in a growing field like AV will not put the audio side in a better position- the individuals are still the same and the problems are still the same. Actually, the amount of attention given to sound would diminish in the relative sense. We have the choice of competing for attention and funding while sharing membership with our competitors within an expanded IASA, a specialised organisation catering for the problems of sound as such, i.e. not necessarily connected to AV.

The problems facing the sound archiving community are real, and the source value of sound recordings is under constant attack: during recent negotiations as to new standards for HDTV (High Definition Television) it was claimed to be unimportant if films in a once- and- for- all conversion to the new format were screened at 25 frames/sec rather than the 24 frames they were recorded in. Only one delegation had done their homework and opposed, due to the transposition of the sound track which would be falsifying the rendition of e.g. voice and music. Another example serves to show that IASA is not yet, even by its present members, regarded as the natural organisation of reference. At least two major archives have been forced to accept digitisation to certain standards in their preservation work. However, none of them thought of asking or referring to the opinion of IASA of its Technical Committee when arguing against short-sighted digitisation projects.

Obviously we need to have international cooperation in fora such as the Technical Coordinating Committee which organises the Joint Technical Symposia, and we must pool forces where it is useful in order to achieve a common goal. However, although it is imperative to learn from the experiences of the moving-image field in preservation of magnetic or even optical soundtracks, I would not like to have to yield to a standard imposed by the conditions of the film or video medium, in the case where the audio is alone. And in case digitisation became an issue for some international standards body, I would like to discuss and argue audio's case in the complete international forum rather than having to make do with the internal forum of an expanded IASA. ISO or CCITT would expect an organisation like the expanded IASA to have its house in order before going to international meetings, and this means there cannot be split opinions. On the other hand, the result of continued disagreement within an expanded IASA would be either that IASA were silent on the issue (to the detriment of the archival community) or an internal split.

We have to remember how IASA was created: a number of music libraries found that they had holdings that were not in printed form, they were sound recordings. And from being a committee on the special problems of sound recordings in libraries, along with greater insight into the matter came the realisation that it was possible to make a delimitation: there were greater similarities between the departments of different libraries holding sound recordings than there were between such departments and other parts of their own library. The time was ripe to create a separate association.

If the need to assist member archives with their AV problems is real, then it is logical to make a debut in the field by immediately creating a dedicated committee, and AV committee. Members would be representatives of those archives which are presently IASA members who have the problems. Once this committee were formed it would be possible to tell the archiving community of this pooling of knowledge and to encourage joining IASA.

To sum up, I feel that it is definitely too early to give up the specialisation which seems necessary to achieve in-depth treatment of those problems that are peculiar to sound taken alone. These problems have not yet been solved, and their solution is not dependent upon membership by archives who mainly cater for sound- with- moving- images. And anyway, where is the logic in attempting to have just one organisation catering for all the problems of AV archiving— archives would still have to be members or at least have staff who are members of AES, ICA or other dedicated organisations. And even the empire builders would not want to take on these organisations as well?

On the other hand, even the IASA we know does need to have a more professional profile which also means advertising the strength of IASA as a body. That professionalism would be noted more widely internationally, if relevant activities undertaken by IASA or due to IASA contacts were promoted as IASA activities and performed in close contact with the relevant committees.

IASA FUTURE AND EXTERNAL RELATIONS

Helen P. Harrison, Past President, IASA

During the Canberra General Assembly the proposals for Constitutional amendments-circulated to all members in July 1992 were discussed at length. Most of the 'cosmetic' amendments were accepted and passed and the Constitution (1992) reflects this. However, some of the major amendments were passed back for further consideration- these were the ones concerned with an expansion of IASA's interests to include audiovisual archives in addition to IASA's primary concern with sound archives.

The reasons for passing them back were surprising to anyone who has worked in IASA over the years- namely that there had not been enough discussion and there was a general lack of information about the reasons for the move.

Even a brief look at the history of the discussions belies this view. Let us attempt to clarify the issue by looking at the history and repeating some of the arguments which have been used for and against.

There were several issues in the draft amendments, but discussion in Canberra centered around an expansion of IASA's interests in audiovisual archives which contain sound documents. Audiovisual archives may be said to have entered the group consciousness of IASA when we first joined the Round Table on Audiovisual Records, an organisation which operates under the auspices of UNESCO. The Round Table was formed in 1979 and has had a membership consisting of IASA, FIAT, FIAF, and the Audiovisual Committees of IFLA and ICA. It is through our membership of the Round Table that interest in audiovisual matters is nourished. We discuss mutual problems with our colleagues in the other Associations as well as less formally during the year. In the mid- 1980's, the Round Table began to realise that certain archives were not able to find representation in any of the constituent Associations. These are the general audiovisual archives which contain film, video, sound, and sometimes photographic material. For several reasons a growing number of archives containing audiovisual materials find themselves without an international Association to represent their interests.

As a result of these indications and because many IASA archives are also audiovisual archives, the Board of IASA began to consider what could be done to help them and others. One option was an expansion of interests to include audiovisual materials in addition to our specialist, interest in sound materials. Initial non-binding proposals, more floating of ideas, were introduced to the membership and discussed in detail with our Round Table colleagues in the late 1980's. The Board considered the issue as early as 1986 when our colleagues in Austria, France and the Netherlands began to widen their scope and extend their interests into audiovisual archives.

In November 1986 at the Stuttgart Executive Board meeting, the Secretary General was asked to produce a report for the membership and IASA opened the debate in the Amsterdam conference in 1987 both in the content of the conference where several papers concerned AV archives, and in the General Assembly. (Phonographic Bulletin No. 49, 1987).

Vienna Conference 1988

In 1988 the debate continued at the Vienna conference in September at a session entitled the Future of IASA. This had presentations from four speakers and because of the interest it generated a second session was included in the Vienna conference. It was decided not to print the discussion in the Phonographic Bulletin; instead they were printed separately as the Future of IASA and sent to all members in May 1989 asking for reactions and comments as well as to generate further discussion at the Oxford conference in August 1989. Two papers from Vienna on the discussion by Hans Bosma and Rainer Hubert were printed in Phonographic Bulletin No. 53, March 1989.

The primary purpose in forming the Association in 1969 was to establish a body of like minded people with similar aims to function as an intermediary for international cooperation between archives which preserve recorded sound documents. The Association is actively involved in the preservation, organisation and use of sound recordings, techniques of recording and methods of reproducing sound in all fields in which the audio medium is used and in all subjects relating to the professional work of sound archives and archivists, but the changing emphasis of our interests towards audiovisual archives has already been noted several times during previous conferences.

Hans Bosma thought there were clear signals that many members collect not only sound recordings but also other audiovisual materials and cannot find an international platform for discussion or for information exchange. At the Stockholm conference in 1986, France, Austria, and the Netherlands announced that they had widened their scope to audiovisual materials and felt IASA could not meet their needs in this field. Also other organisations such as FIAF or FIAT are, for several reasons, not appropriate organisations for many audiovisual archives to join. Rainer Hubert looked at our relations with other organisations and proposed some interesting ideas for future cooperation and even the formation of a parent organisation. This point was taken up in the Round Table and in the Oxford conference.

The ensuing discussion was extensive and only a summary can be given here. The membership at the time recognised that we are sound archivists with increasing ancillary interests, and that changes are necessary to keep IASA as a dynamic organisation: changes in our scope and changes in our structure and organisation to accommodate this extension of our interest. But which should come first? Logically we have to decide what are the aims and objectives of the association and then devise a Constitution which will help to fulfil those objectives.

Hans Bosma posed the main question:

Is IASA willing and able to change its purposes to include all audiovisual materials and is IASA willing and able to act as an association for audiovisual archivists? The answer will be found in clear purposes.

Three suggestions for change emerged:

Oxford conference 1989

During the Oxford conference 1989 a further session was devoted to the Future of IASA. One member had taken the trouble to send a detailed written comment after the first paper was circulated and his comments formed a substantial part of the discussions at the Oxford session. We also had representatives from FIAF and FIAT who added to the discussion on external relations. The resulting discussion was printed in a second separate leaflet Future of IASA Part 2 and was sent to all members in October 1989.

These discussion papers covered a wide range of topics concerning IASA structure, scope and external relations- topics which have exercised the Association ever since, as it appears. At each stage IASA members were asked and encouraged to take part in the debate, but the response was unfortunately very sparse- perhaps a result of busy working lives, or worse, apathy.

At the Oxford conference General Assembly, a Board resolution was presented to the membership. Three of the points are particularly relevant to the present discussion:

These resolutions were dated 1 September 1989.

One member argued that it was more sensible for institutions and individuals who are involved in different media to be members of several international organisations, and counter arguments came from the National Film and Sound Archive in Canberra, Australia, and the National Archives Committee, the majority of who maintain a function-based rather than a media-based institution. The National Archives Committee argue that the majority of their member institutions are already de facto audiovisual archive collections. There is a trend towards the development of multi-media archives whether for practical, economic or philosophical reasons.

The various branches of audiovisual archiving have so much in common that it is in everyone's interest to recognise realities and the capitalise on inherent strengths. At stake in the long run is the recognition and perhaps survival of our profession and the development of a coherent and well-articulated body of theory on which recognition must ultimately rest.

Following the Oxford conference discussions, work began on drafting a new Constitution. These and other developments were summarised in the President's report to the General Assembly at Ottawa in 1990.

Sopron conference 1991