2002

Annual Conference: Arhus, Denmark (IASA solo conference)

President: Crispin Jewitt, British Library National Sound Archive, UK. Kurt Deggeller, MEMORIAV, Switzerland

Editor: Chris Clark, The British Library National Sound Archive,London, UK. Ilse Assmann, The South African Broadcast Corporation Sound Archive, Auckland Park, South Africa

IASA Journal, No 19, June 2002, p 4-5

President's letter

This is my final President's letter to you, so it provides the opportunity for me to reflect on how the Association has developed over the last three years, and on the opportunities and challenges we face over the coming period.

Our membership continues to grow: we passed 400 recently, and it is most encouraging to see colleagues in Asia and Africa joining the Association. Since the Latin American Seminar in Mexico City last November we have welcomed new members in Venezuela, Mexico and Chile, while we now have members in Thailand and Pakistan to add to our Asian membership. Another significant group of new members is from North America, so we can see that IASA is growing healthily as a world-wide organisation. There is still much to do. I have recently written personally to colleagues working in radio archives in Asia setting out the benefits of IASA membership and encouraging them to join. We are also working to develop appropriate structures to support our members in Africa and their particular needs. At present the Executive Board has decided that the most practical way of doing this is to continue offering support on an individual basis through helping with the costs of attending the annual conference. We hope, with the 2003 conference being held in South Africa, to establish a regional structure there before too long. We also anticipate that the new Research Archives Section will increasingly provide a focus and support for many of the small institutions among our members.

The new IASA website (http://www.iasa-web.org) is now up and running and this completes the re-design and branding of IASA publications which was initiated by the previous Board. We will be including the existing separate web presence of Branches and Committees in due course, and we anticipate that our website will develop into a rich information resource for our members, and indeed, all concerned with audiovisual archiving.

At the annual meeting in Paris of the Co-ordinating Council of Audiovisual Archive Associations (CCAAA) we welcomed as new members the South East Asia & Pacific Audiovisual Archives Association (SEAPAVAA) and the Association of Moving Image Archivists (AMIA). CCAAA now includes all of the key international associations in our field of work and provides the opportunity to speak out publicly with one voice on policy issues such as copyright and access, the preservation of heritage, and professional education.

I have recently travelled to Denmark for our own Executive Board, and to Laos for the SEAPAVAA annual conference, but I did not need to travel so far for the regular IASA Radio Sound Archivists' meeting with FIAT, which took place recently in London. This well-attended meeting was hosted by the BBC and provided the opportunity to learn about the European PRESTO project which has done some path-finding work quantifying the challenges posed by the need to move very large analogue archival holdings into the digital domain. From my own perspective this meeting was also important in bringing together professionals working in both the library and the AV archive sectors to recognise the extent to which they can share common solutions to some major challenges. This three-day meeting, which included site visits to BBC facilities as well as to the BL NSA's own technical and conservation operation, was widely regarded a success. It was good to see the BBC active in lASA's affairs again. More about PRESTO can be learned at http://presto.joanneum.ac.at

Our annual conference this year is to be held in Aarhus, Denmark, 15th – 19th September. The theme is Digital Asset Management and Preservation and there will be presentations of relevance to all kinds of AV archives, large and small. The results of this year's elections for a new Executive Board will be announced during the General Assembly and so we will know the composition of the new team which will serve IASA for the next three years. Your next letter in this journal will be from our new President. Aarhus is a charming city and a most pleasant place to spend a week with friends. I look forward to renewing old friendships and making new ones in September at our annual meeting.

Crispin Jewitt

28th June 2002

Printable version

IASA Journal, No 20, December 2002, p 3-4

President's letter

It is a great pleasure for me to write this, the first president's letter of the newly elected Executive Board, and on this occasion I would like to propose some priorities for the work of IASA over the next three years. You are most welcome to send feedback to my e-mail address kurt.deggeller@memoriav.ch.

The programme, which has already been determined for the coming months and years, has some inherent focal points. The 2003 Conference is one of them. If this conference is to be a success, the maximum possible exchange of information with our colleagues from Africa must be an objective. From our point of view, two key input areas need to be addressed. The first is financial: we have to ensure that our colleagues can travel to Pretoria. The second is more conceptual: we need to modify our "northern hemisphere" or "western world" view of the problems of audiovisual archiving and listen carefully to what our colleagues from other areas have to say. IASA has been asked to participate in training seminars on audiovisual archiving in Mexico and the Caribbean in collaboration with FIAT/IFTA (The International Federation of Television Archives). These invitations show that from the periphery our two organisations are considered to be close in terms of the scope of work and complementary to each other. We need to take this further with our colleagues from IFTA. In any case, the important difference between the aims of archiving in broadcasting and the aims of what are known as "heritage institutions" has to be clearly defined. However, we still have to consider that broadcast programmes have become a major source of information that shapes our vision of the world, of history and of culture.

The 2003 programme (the Annual Conference, the above seminars, and the traditional meeting in spring with FIAT/IFTA on broadcasting problems) will take us to the limit, or even beyond the limit, of our capabilities as an organisation based on volunteers. It is hardly imaginable that your institution would pay for all these activities, and IASA does not currently have the funds to cover these costs. We need to find new solutions quite quickly, perhaps in association with other international organisations that are active in our field. Some years ago, after a long period of reflection and discussion, IASA changed its name from International Association of Sound Archives to International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives. The rather confusing formula “sound and audiovisual" was a political compromise and has - at least to my mind - clearly prioritised sound, which is reflected by the topics treated in the annual conferences since then.

The confusion is probably also owing to the fact that "audiovisual" has never been defined clearly, and that there is no clear delimitation between our activities and those of our sister organisations FIAT (Television Archives), FIAF (Film Archives) and AMIA (Moving Image Archives). I think it is high time we worked on these problems. In my experience as director of the Association for the Preservation of the Audiovisual Heritage of Switzerland (Memoriav), I have some ideas on how we could clarify the situation. But once again, this problem can be resolved only in co-operation with the other associations.

Another objective in the same field is our relationship with very large organisations such as ICA (Archives), IFLA (Library Associations) and ICOM (Museums).These represent the large community of heritage institutions, which have a central role in the preservation of people's memory of their own society and culture. The audiovisual part of this heritage has clearly been neglected in this context until now. It will be our task to offer these large institutions, and individuals, specialised knowledge and competence when required. The invitation by ICA to organise workshops during their next General Conference in 2004 in Vienna is the first very important step in this direction.

One of our main tasks over the next three years will be to build up reasonable models for co-operation in the main fields of our activities. The Co-ordinating Council of Audiovisual Archives Associations (CCAAA) is an excellent platform from which to take this task forward. We should not forget that CCAAA owes its existence mainly to Crispin Jewitt, who drafted its Terms of Reference and has pressed us to participate in the building up of the organisation.

I wish all our members everything of the best for 2003, and I hope to meet you all in Pretoria.

Kurt Deggeller

17 December 2002

Printable version

IASA Journal, No 20, December 2002, p 5-20

Article

Do they mean us as well? Managing Knowledge as a Digital Asset

Chris Clark, British Library National Sound Archive

Keynote address to the IASA Conference. Aarhus, 2002

Management challenges for the 21st Century is the title of a book recently written by the acclaimed management theorist Peter Drucker. Among its many predictions we find:

"The most valuable assets of a 20th century company were its productionequipment. The most valuable asset of a 2lst- century institution, whether business or non-business, will be its knowledge workers and their productivity." (1)

We spend a lot of our time at IASA conferences talking about our collections and the processes we have devised to preserve them and make them available but apart from the occasional paper about training, we have a tendency to ignore ourselves, the knowledge workers, who are carrying out all of this marvellous work. If we believe Peter Drucker's prediction, "we ourselves" have recently acquired considerably greater asset value within our respective institutions. That is the theory and that is the governing hypothesis for this presentation.

I will not attempt to define knowledge as this is not a philosophy symposium but a useful working definition for the purposes of this presentation comes from Tony Brewer, a former knowledge management consultant in the U.K. He defines knowledge as "a packet of information in a wrapping of context that gives it relevance and significance" (2). Knowledge serves as a catalyst: there must be a transfer. As a result of obtaining knowledge, there may be some measurable outcome, good or bad. On the basis of this definition, thousands of companies have adopted as part of their mission statement "delivering the right information to the right people at the right time". I think we all suspect that it's not as simple as this. To begin with, there are two categories of knowledge: tacit, the knowledge we carry around in our heads and explicit, that which we choose to make available, typically in a form that can be documented and archived. We will see that the tacit category presents some stiff challenges to management.

As audiovisual archivists, the range of skills and depth of knowledge expected of us has always been varied and demanding - that is part of the attraction of the job. Our present conference themes, preservation and digital asset management, mark the extremes of that range: at one end is the commitment to the ethics of archiving, ensuring that documents - in the widest sense of that word - are preserved unchanged indefinitely. (One might say that here we are taking care of our liabilities). At the other extreme is the need to generate business from the exploitation of those documents, which may mean creating copies or versions of the originals for a multiplicity of purposes and audiences. This is what I understand to be the locus of asset management (3).The two extremes could be self-supporting in that what is selected for access could also be prioritised for preservation but this cannot be assumed and more often, I think, that they may be in conflict.

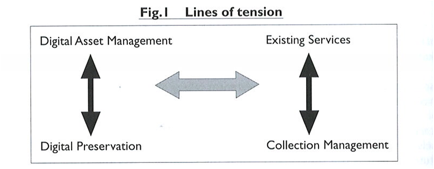

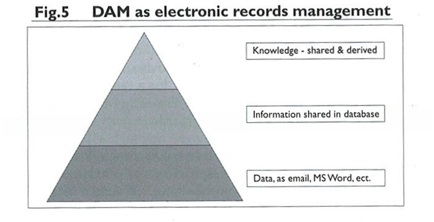

The advent of digital technology has stretched the range of skills and knowledge expected of us. But there is now a real tension, not just between these two extremes on the digital axis, but between this axis and its non-digital parallel [see Fig. I]. As our organisations attempt to manage the processes that correspond to existing services and collection management while introducing, as quickly as possible, new processes for digital it has become clear that resources cannot be stretched to such a degree. We need help.

And our users, increasingly interested in what we are up to behind the scenes, have noticed. In a recent study of culture at the end of the last century, Grammars of Creation, the polymath and literary critic George Steiner remarked that libraries, particularly national libraries, now seemed to be "part shrine and part futurama" (4); fading museum pieces and heritage in one corner, alluring electronic distractions in the other. Indeed, it often seems of late as though the values of show business have been allowed into our archival stores.

The hope is that this will be a temporary perception while things settle down, but through its close association with technology, the electronic or digital side to our work advances at a vertiginous rate and it is often difficult to identify the components that will endure. However, I think that the position may be more certain for digital preservation than it is for access; digital asset management (DAM, for short) as a technical application, from what I have read, looks like a temporary fixation until the next 'big idea' comes along.

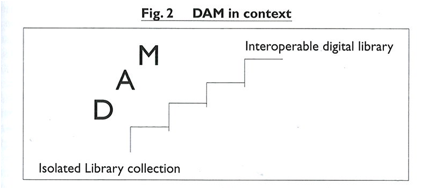

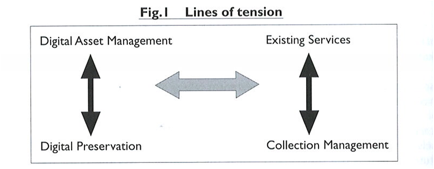

So you can see, I am not about to promote DAM and its numerous providers as the new panacea for audiovisual archives though it does offer some obvious benefits. Most of the DAM systems I know about and that have been applied to audiovisual archives are in broadcasting companies, such as the BBC. As I work in a national library that, at the moment, barely recognises the term this hardly qualifies me as an enlightened spokesperson for DAM. Instead, I want to place digital asset management in the broader context of knowledge management, to explore around the subject in order to define its relationship to the work of audio-visual archives. In particular, I want to place it within the current process of change that sees a typical IASA institution moving from the isolation of an idiosyncratically described collection that people have to visit towards the more generalised exposure of an interoperable digital library whose users link in from the Web.

>

I prefer to use the term "library" rather than archives in most of this presentation. I believe that our collections, which are indeed archival in terms of preservation and storage, will increasingly be accessed alongside other kinds of media delivered by web-based library services and alongside or as a part of services that have nothing to do with libraries and archives. In this respect I will mention some of the development work on web tools for discovery and retrieval carried out mostly in the United States that builds on mark-up languages derived from practices developed by the library and archive community.

Do they mean us as well? By "us" I mean people who mostly work for institutions, but the new technology we have been encountering, and to which we are trying to adapt, causes problems for institutions and their systematised ways of working, whereas it tends to liberate individual action and development: hence the emphasis on the individual in my title.

I want to continue by reading a passage from a recent work of fiction. The author is W.G. Sebald, a German writer who lived for many years in England and who taught at the University of East Anglia until he was killed in a road accident last December. His writing consists of an astonishing blend of fact and fiction. In his last novel, Austerlitz, a Jewish evacuee by that name, now an architectural historian, attempts to re-discover his past through a blend of chance, hallucination and deliberate research. For his research, he makes regular use of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris. Here is his account of working in the old building: the date would be around 1950:

"In the week I went daily to the Bibliothèque Nationale in the rue Richelieu, and usually remained in my place there until evening, in silent solidarity with the many others immersed in their intellectual labours, losing myself in the small print of the footnotes to the works I was reading, in the books I found mentioned in those notes, then in the footnotes to those books in their own turn, and so escaping from factual, scholarly accounts to the strangest of details, in a kind of continual regression expressed in the form of my own marginal remarks and glosses, which increasingly diverged into the most varied and impenetrable of ramifications. My neighbour was usually a gentleman with carefully trimmed hair and sleeve protectors, who had been working for decades on an encyclopaedia of church history, a project which had now reached the letter K, so that it was obvious he would never be able to complete it.

Without the slightest hesitation, and never making any corrections, he filled in one after another of his index cards in tiny copperplate handwriting, subsequently setting them out in front of him in meticulous order. Some years later, said Austerlitz, when I was watching a short black and white film about the Bibliothèque Nationale and saw messages racing by pneumatic post from the reading-rooms to the stacks, along what might be described as the library's nervous system, it struck me that the scholars, together with the whole apparatus of the library, formed an immensely complex and constantly evolving creature which had to be fed with myriads of words, in order to bring forth myriads of words in its own turn. I think that this film, which I only saw once but which assumed ever more monstrous and fantastic dimensions in my imagination, was entitled Toute la mémoire du monde and was made by Alain Resnais. Even before then my mind often dwelt on the question of whether there in the reading-room of the library, which was full of quiet humming, rustling and clearing of throats, I was on the Islands of the Blest or, on the contrary, in a penal colony." (5)

Quoting from a work of fiction might seem an inappropriate way to begin this conference given the real and tangible concerns of conservation and asset management, but when I read it a few months ago this personal impression of a very large library, its ambition and its systems for managing knowledge rang all sorts of bells. It sets the scene for the remainder of this address more eloquently than I can.

I'll return to the 'penal colony/Island of the Blest' analogy later. Meanwhile, there are several themes to be drawn from this passage I have just read out that I will try to develop:

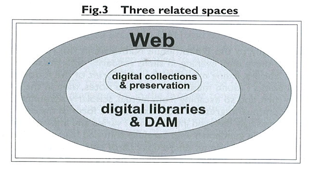

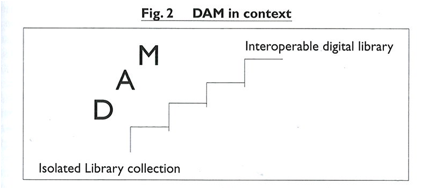

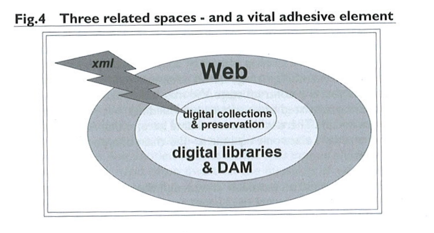

- The interaction of three separate spaces: the personal space of Austerlitz in his web of footnotes; the surroundings of the library reading room; and its portrayal in the medium of film that subsequently projects an exaggerated image within the narrator's memory. Each of these can equate to personal, institutional and mediated knowledge systems respectively. In this talk I will be considering our conference themes - conservation and digital asset management - within an abstract working landscape that, likewise, includes three related spaces: digital collections (including preservation); digital libraries (including DAM) and the Web.

- the contrasted working practices of Austerlitz with his disorderly marginal notes and his neighbour's precisely ordered but never to be completed index: this will be developed through a view of individual knowledge systems, such as weblogs and collaborative information systems that are thriving and which contrast starkly with corporate knowledge systems that, however carefully managed, tend to remain unfinished, mis-judge the audience or never even get past the contract stage. We may have been able to define the audience when that audience consisted of visitors to our buildings, but audiences on the Web are resolutely unpredictable. There is also a sub-theme here, in that Austerlitz's footnote-driven research mirrors today's electronic equivalent - the chain of hyperlinks by which we typically navigate the Web.

- the world of knowledge as an insatiable creature ('informavores', as they are known in certain parts of the West Coast of the United States) fed by technology driven systems. Back in 1950 the pinnacle of library technology was pneumatic post and a decent step-ladder: now we have electronic mail and super archives: we'll look at some American projects involved with data mining and resource linking as well as D-Space and the Wayback Machine, just two of today's attempts to encapsulate "toute la mémoire du monde" (or at least a significant part of it).

- From our standpoint fifty years later, what was not yet a reality for Austerlitz is also important. The library he used was self-contained, subsidised, and independent. Since then we have seen a gradual evolution in the library and archive world towards mutual dependencies, to a diffusion of roles and this is now having a profound impact on the way we do things, especially on the digital axis where there is greater dependence on partnerships and external sources of money.

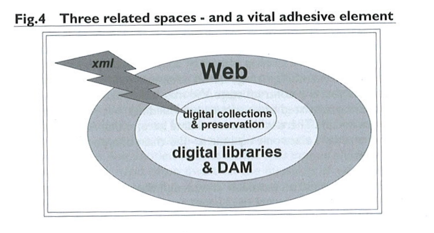

The rest of this presentation will develop these four themes and mostly takes the form of a record of ideas and projects I've encountered on a journey taken over the last six months through a landscape made up of the three related spaces I've already drawn - digital collections, digital libraries, and the Web. It's a landscape in which our work as individuals, and as individuals within groups can find the inspiration to work together in order to attempt to preserve collections on the scale we have set out to achieve. It's a landscape in which the provision and discovery of knowledge in electronic form can be managed and in which our institutions and the people that work in them can thrive rather than merely survive. And if these three spaces seem today like separate spheres of activity, physically, as well as logically, then as our work becomes more diffuse and collaborative, so the spaces become more homogeneous. There is one vital ingredient that needs to be added to our scheme: metadata, without which the content in our collections remains a jumble of bits. Metadata in the specific and, I believe, soon to be ubiquitous guise of the extensible mark-up language, or xml.

Digital collections

Our journey through this knowledge management landscape starts in familiar territory with the stuff in our collections: we recognise most of the landmarks but are we clear about the terminology? In the light of earlier digitisation projects in the United States the terms "digital collection" and "digital library" were often confused. Since then there has been an attempt to separate the two so that digital collections are now usually defined as the raw content where the emphasis is on its long-term preservation; whereas digital libraries are systems that "make digital collections come alive through various mediating layers, such as catalogues and Web sites.

The main features of digital collections can be listed as follows:

- They contain raw, unmediated data plus metadata that is born-digital or digitised from older originals. (Of course, this raw data may represent works that are rich in stored knowledge, but to the storage system they will just be a jumble of digits).

- We're actually getting expert at digitising (there are plenty of standards): we are now seeing a commitment to optimising practice after the first round of projects that were by and large experimental.

- Commitment to preservation (or safeguarding for perpetuity). The major influence on thinking and planning in this area is the conceptual framework developed by NASA, OAIS (Reference Model for an Open Archival Information System). It's official Web site is ssdoo.gsfc.nasa.gov/nost/isoas/ where you can read about its history and reports of workshops.

- Numerous formats (archive and access audio formats, streamable media, MS Office files, Acrobat PDF) all prone to obsolescence, so we expect to have to adopt a mix of preservation strategies. (This is the real challenge. Computer science progresses by replacement, research by accumulation. The two are in real tension. I doubt this is on Peter Drucker's list of 21st century management challenges, but it is certainly on ours).

Digital preservation is a growth area in the professional literature. How do you keep up? At the British Library our Digital Preservation Co-ordinator introduced a very simple measure called a reading group. Every month each one in the group covers two or three of the main web-based journals that cover digital preservation (e.g. RLG Digi-News, First Monday, CLIR Issues) and brings relevant citations to a meeting of the group where the articles are discussed. This ensures that the ground is covered, knowledge is shared, and ideas are better understood through being articulated to a peer group that includes managers. I recommend it, even though your startling discoveries may conflict with corporate programmes already underway.

Some of the projects we have been following are:

- LOCKSS (Lots Of Copies Keeps Stuff Safe) http://lockss.stanford.edu/

- OCLC/RLG Working Group on Preservation Metadata

- OCLC/RLG Working Group on Attributes of a Trusted Digital Repository

The group has also been looking closely at some examples of very large and successful digital collections on the Web, all of which contain technical information about how they were created and how they are maintained:

- Brewster Kahle's Wayback Machine - //www.archive.org/

the archive of the Internet that has set itself a very big goal: Universal Access to All Human Knowledge.

- Pandora http://pandora.nla.gov.au/

the guardian of Australian websites, that Kevin Bradley spoke about at our conference in London last year

- MIT D- Space

a superarchive - collecting research material from nearly every professor at the institute http://chronicle.com/free/v48/i43/43a02901 .htm (Chronicle of Higher Education 5/7/2002)

Masses of data are being compiled and preserved here. All seem capable of dealing with infinite expansion, but alarm bells have recently sounded at Electronic Records Archive (ERA) run by the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in the United States. NARA recently admitted to becoming overwhelmed by the annual growth rate of 36.5 billion email messages that it is expected to manage and has made an open request for the computer industry to help. (6)

As we sigh in recognition and sympathy, we'll leave the digital collection space and move on.

Digital libraries

Digital libraries are what we, and the community of users, make of digital collections. They consist of various layered services and products based on the collections that taken together as an aggregation, over time, may be greater than the sum of the individual objects held in the collection. The best list I've encountered of these layered services appeared in Lorcan Dempsey's Scientific, Industrial, and Cultural Heritage: a shared approach (7). It includes:

- Disclosure services (catalogues and other finding aids, such as GIS)

- Content delivery services (streamed audio examples) Rights management services

- Ratings and recommended systems (i.e. such as you find at Amazon.com)

And to this list we could add material mediated for different user groups, such as schools or higher education.

This is where DAM makes its appearance, for it can potentially deliver most, if not all, of these services.

But first I want to say more about digital libraries in general.

Digital libraries are only just beginning to emerge, and not all are under the control of the library professionals. A good example is the Perseus Project at Tufts University (8). This Project is computationally linking together multiple resources, so you can take a biographical dictionary and link names to maps or mentions of place names in literary works. It has now added OAI compliance, which means that from Perseus you can harvest metadata (typically object descriptions) from registered OAI repositories, of which there are now well over one hundred. (OAI is the Open Archives Initiative that allows metadata harvesting between organisations - it requires a paper to itself).

Other OAI registered digital library projects include the European Commission -funded Cyclades project and Kepler's home page. A characteristic of these interactive resources is that they deliberately encourage users to compile their own digital libraries and collections in order to generate new material. This new material will, sooner or later, end up in a library, that will then recycle it to the world as a new born-digital object — and so the interactive cycle of content will continue, gradually erasing any notion of a definitive edition or canonic text and, by breaking the familiar author - publisher - distributor - library chain, and eroding the basis for copyright. But that's another story that we'll glimpse later on.

Data mining is a growing activity that may be enabled by digital libraries. This involves amassing vast quantities of data and then applying computational resources to look for patterns and relationships in it. The more data you have, the more interesting the results. In essence, data mining creates new knowledge out of raw data. Some of what you can do on Perseus can be classed as data mining, and it's certainly widespread in disciplines such as astronomy. There are also possibilities, I imagine, for employing it in the study of recorded words and music.

DAM

Although it is more selective than data mining, there are some parallels between what an organisation can do with a DAM system and what a researcher can do with a data mining tool in that both involve the reuse of existing content. The bibliography connected with DAM is much more extensive than I had expected and it's mostly American. Despite initial doubts it became apparent fairly quickly that DAM is actually something new for IASA: the possibility of multiple re-use of our collection material and maybe some financial gain. The Gistics Digital Asset Management Market Report 2002 (the Bible of the DAM 'd) is more explicit:

digital asset management represents a business strategy for accelerating business-process cycle times. (9)

This kind of talk will be foreign to most IASA members, so let me say that my understanding of where it fits in our community is somewhere between this hard business definition and the digital library concepts we have just been talking about. The most useful slogan seems to be one adopted by Gistics - Unlocking the value of the digital master.

DAM is now a $60 billion dollar business with more than 600 DAM solution providers ranging from Cumulus for the individual user at around $ 100 to IBM projects for big companies costing $5million, with Artesia deployments hovering at around the $100,000 mark. DAM may offer the prospect of a quick win for the company that embraces it, but it may not be a cheap one. And such is the pace at which new technology moves, people are already writing about the demise of DAM around 2005 as it evolves into a set of features within generic content management tools.

The term 'digital asset management' appears for the first time about ten years ago. CNN and Discovery Communications were early customers using DAM to manage their vast video libraries; recent converts include Coca-Cola and DaimlerChrysler who were quick to appreciate the savings to be made by adjusting digitised copies of old advertising footage, for example the hippie era classic "I'd like to buy the world a Coke", rather than create something equally innovative but very expensive. The BBC [specifically BBC Technology, a commercial subsidiary of the BBC] expects its Artesia TEAMS enterprise digital asset management solution to be used in support of commercial sales, developing integrated solutions for "streamlining the production, management and distribution of rich media programming across existing and emerging channels."

Other possible commercial applications of DAM in audiovisual archives might see it included as part of a trusted digital repository package offered, for a fee, to sectors of the recording industry. My own organisation is thinking about this. The ability to re-purpose material also lends itself to supplying content to the educational sector.

A common feature of all DAM systems I've come across is the emphasis on recycling assets, sustaining knowledge and content to be licensed again. There's nothing startlingly revolutionary about the idea of one input, many outputs. Everyone here will have understood that a digital master may be copied in several ways: as a streamed file, as a compressed segment, etc. But in the context of DAM, digital masters represent a type of digital asset that may contain sufficient data to produce dozens or hundreds of individual reuses.

The extent to which we can engage in this frenzy of recycling and re-purposing will, of course, depend on whether we own the rights or a license to do so. But also, since we have introduced the word 'asset' in this conference in place of the more common word collection or 'holdings', we will need to consider some additional bureaucratic measures. We all have digital objects - but they will only be classed as assets if an auditor can answer questions such as:

- Has the archive documented the object's development costs?

- Has the archive documented how the object has directly contributed to a sale or an identifiable cost saving?

- Has the archive taken prudent measures to ensure the object is protected from misuse?

These are the specialised data management facilities that a DAM system will provide and which your current cataloguing system will not, in case you were wondering if there is a difference.

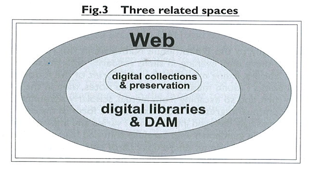

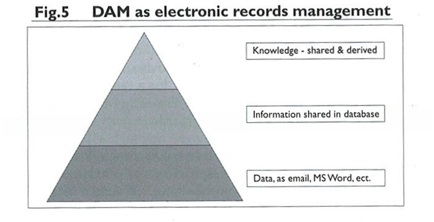

I think there is another important dimension to our engagement with DAM, and that is its application to the knowledge that exists in an organisation, whether categorised as explicit or tacit. This could be described as digital asset management in the form of electronic records management and it sits alongside the commercial functionality just described.

My own organisation, The British Library, is currently running a pilot records management project - ERDM (Electronic Records & Document Management). It has been introduced in the department that deals with the management of the building - maintenance contracts, security systems, and so forth. It went live in January 2002.At one level (Records) it consists of a compilation of data, such as emails, file notes in MS Word, etc. (In some organisations .wav files are kept of telephone transactions). At the next level (Information), the data are linked in a database structure. Typical outputs for the department are who transacted with whom, when and how much money was involved, what negotiations took place. In other words, it's a record of business interactions.

Information, if filed and tagged correctly, can then become 'knowledge', that is knowledge about a particular set of preferences, reasons for the success of a particular service or product. In the next phase of ERDM the system will attempt to embrace knowledge throughout the organisation. This is where they expect to encounter resistance.

Working colleagues are often respected and revered on account of the knowledge they carry around in their heads, their tacit or innate knowledge. How many of us routinely refer enquiries to staff known to carry in-depth specialist knowledge rather than seek answers in "the system"? As John Perry Barlow recently said:

A five-minute conversation with the right person can be more enlightening than five hours online. The most powerful search engines out there are other people.

How we miss those colleagues when they retire. Wouldn't it be better to hold this personal information in refreshable perpetuity for future generations of staff? Managers think this will help with succession planning. Their staff may not because they believe their knowledge gives them a special edge. Knowledge, in some contexts, is power.

There's a curious irony at play here. Individuals may be reluctant to share their knowledge within an organisation, but it is difficult to curb their enthusiasm when invited to contribute to the Web. Maybe there's a lesson for managers here. But maybe there is an alternative technical solution that could combine localised knowledge management with the universality of the Web. David Karger at MIT has had such an idea and I would encourage you to take a look at his Haystack software project ( 10) as this has been designed with no particular market in mind. Haystack is for individuals, whatever their status, and can be evolved according to personal preference. The bonus for that person's manager is that the information and knowledge held in individual Haystacks can be shared, not just within the organisation but over the Web.

Which is where we enter our third space...

The Web

I don't want to say too much about the Web as this was the subject of Trond Valberg's keynote speech to the Singapore Conference two years ago and he covered a lot of the ground. I just wanted to make some comments here that relate directly to the management of knowledge, but also would like to emphasise that it makes no sense to consider digital preservation and digital asset management without taking account of the Web. This is where our main competition lies: you want catalogues of sound recordings - the Web has thousands; you want profiles of recording artists? However obscure - you'll find something.

Firstly the architecture of the Web, summed up neatly by Doc Searls (II):

nobody owns it, everybody can use it, anybody can improve it.

It is perhaps the greatest engineering marvel on a massive scale the world has seen, but it has happened with no centralised management or control. You add a link and you become part of it: if the link is broken you become invisible. If the link you are following is broken you link to somewhere else, and if the something you are looking for is not there, you're entitled to create it without asking anyone's permission. No wonder people have flocked to it in droves leaving some learning institutions to wonder if they need ever purchase another book.

The links determine the space. A recent book about the Web, Small pieces loosely joined, by David Weinberger (12) discusses the nature of space on the Web in the following terms. Nearness is created by interest and the closest distance between points is measured by relevance. This is why I think we are willing to tolerate the apparent mess that confronts us every time we do a search. Suppose you were looking for how much money was spent on CDs in Denmark last year. I typed into Google "Denmark, CD, sales, 2001 " and in less than one second it found over five thousand pages that match those words. But none of the ten deemed most relevant by Google were right and only at result no.34 did I find the answer. From a traditional business point of view, this is a spectacular failure: someone asked you a question and you gave them 33 wrong answers - you're fired. But this is just the point: the Web is not a business-like environment in which traditional corporate identities and notions of protected scarcity for competitive advantage can expect to thrive (which may partly explain the spectacular business failures we saw in 2001):

those that designed the Web weighed perfection against growth and creativity, and perfection lost (David Weinberger)

It's imperfect and fallible on purpose, just like the people who use it. The information you linked to may not be mediated and authorised, but a person decided it should be there. I think there is some truth in what Weinberger and a number of other people have been saying recently that the Web is not a space full of data, but a space full of the sound of human voices. It's an unprecedented environment for individuals to interact and for knowledge to evolve and be shared. (This is perhaps an over-optimistic view in that it conveniently ignores the fact that English, the Web's principal language, is not everybody's first language).

Therefore individual knowledge sites have mushroomed: some of these are very thorough, not to mention very useful. Take weblogs, for instance. Weblogs (or blogs for short) are free, searchable journals of opinions and links updated daily by an individual or a group and they have become some of the most popular Web sites. David Winer, a blog pioneer from 1996, describes weblogs as

kind of a continual tour, with a human guide who you get to know. ( 13)

They're the nearest the Web gets to a managed information resource in that to be listed and to be listed repeatedly will enhance a site's reputation and thus help locate useful resources.

They are useful gathering points for an abundance of subjects. A very useful knowledge bank about Internet developments, and one of the first to be set up, is Tomalak's Realm (14). It's run by Lawrence Lee for all things related to strategic web design. According to some It's run by Lawrence Lee for all things related to strategic web design. According to some commentators, Blogs are changing the way we use the Internet; we consult a blog in the same way that we pick up the morning newspaper or tune into to the radio new bulletin. There's a dedicated search engine - Daypop, that retrieves pages from 7500 blogs, that's a mere 7.5 percent of what's actually available. (15) Significantly, companies have started hiring professional bloggers.

The presence of large amounts of compelling non-commercial material, such as blogs, was the reason why people flocked to the Web. We can therefore assume that there is a crowd of expectant niche audiences out there at whom we can target our managed collections of unique, non-commercial or public domain recordings. But not everyone is convinced that this kind of opportunity will last. A number of legal experts in the United States are deeply apprehensive about the attitude of the entertainment industry to the Web, or rather to those that use the Web. We've all heard the arguments about peer to peer file sharing and the penalisation of Napster. There's currently a less publicised appeal case Eldred ν Ashcroft that concerns the freedom to republish html versions of public domain literature, the main issue being a constitutional challenge to the recent extension by twenty years to existing and future copyrights. Also known as the "Free the Mouse" case (as in Mickey Mouse), you can follow the story at eldred.cc/

Another interactive source of knowledge to be found on the Web but which evolves by e-mail between subscribers (and at no charge) is the specialist discussion list or listserv. I imagine many here subscribe to a number of these but if you are involved in documentation and metadata developments, then joining XML4Lib, run by Roy Tennant at Berkeley CA is essential (16). There is no competitive aspect to this and experts and novices alike participate and all questions, however basic, will receive an answer (or forty).

Metadata, as we have established, is vital to this whole scheme I've been describing. There have been many contenders for metadata of choice on the Web but I think it is now clear that one metadata format, xml, is going to prevail. For the following reasons:

- XML is the focus of a vast amount of development and standardisation, which in turn results in many software tools and applications that can be re-used for digital libraries. What seems to me a major benefit of xml is that it doesn't make other metadata schema redundant: you can incorporate Dublin Core and MARC within it;

- if something comes along to replace XML, it will be a development of it, not a parallel technology;

- XML is the only networked data description language.

It is also an essential component of the Web's next phase of development, the semantic Web, as described by Tim Berners Lee in the now famous article he wrote for Scientific American last year:

the semantic Web is not a separate Web but an extension of the current one, in which information is given well-defined meaning, better enabling computers and people to work in co-operation. (17)

The Web we know is for people. The semantic web is for people and machines. A new meaning will be given to the phrase "talking book". They'll talk to each other; audio will know it is being listened to...

Before you think all this talk of Web phenomena has deprived me of all good sense, I will start to sum up. In fact there is a very interesting project that could sum up for us. It's called Simile and it's being run at MIT. (18)

Simile is a 4-million dollar project set to last three years and it aims to explore the intersection of three spaces:

- institutional information management and digital asset management

- personal and collaborative information management

- the semantic web

Collaborators are MIT Lab for Computer Science, W3C, MIT Libraries, and the Hewlett-Packard Company. Key technical components are DSpace and Haystack that were mentioned earlier, so there is a clear intention here to try to make metadata uniformity work alongside personal or arbitrary schemas. So you see, Austerlitz and his orderly neighbour can work together.

In advancing the case for the individual in this talk (Do they mean us as well?), I have not sought to deny a future for institutions such as the Bibliothèque Nationale de France or the British Library. These have only just been built as part of a phase of library and museum building that is unprecedented in history. Clearly they have a long and productive future but it is one that will be different to work in and to work for. Libraries and audiovisual archives have already moved well beyond the "quiet humming" of the reading rooms visited by Austerlitz and the task of preserving as great a variety and quantity of material for future generations, just in case it is needed. Existing alongside the Web some of the old certainties have been challenged and our institutions need to draw support not only from formal partnerships but also from the kinds of informal networking that I have described. Our institutions therefore need to provide frameworks, such as DAM systems, that can support this so that knowledge flows freely between individuals and groups of individuals that exhibit complementary sets of skills, thereby fostering the kinds of innovation that enable them to move forward. They will certainly have to learn to relate to a networked environment and understand better how to present a corporate front to the highly individualistic Web. Fortunately, we have in libraries and archives a history of collaborative working and shared activity that extends back over four decades. In our PC dominated workplace the lines of communication by which we derive knowledge or extend our influence are increasingly horizontal and between institutions rather than vertical within a single institution. This, I maintain, is a liberating notion.

I have argued, in agreement with an acknowledged expert, that knowledge workers (like those of you reading this) represent as valuable, an asset as our collections, and the expensive systems we install. I do not have a management prescription for dealing with this outbreak of individualism, but it seems to me that if the productivity of knowledge workers has become a most valued asset, then managers need to develop more sophisticated techniques for assessing success or failure, such as the measurement of outcomes, rather than relying on the routine reporting and adjustment of inputs and outputs. This is too mechanised. The main space in which our institutions will develop in future is the Web. Therefore, our value as assets might also be measured by the extent to which we have networked our knowledge: I link, therefore I am.

Finally, if you will recall the quotation from Sebald, his architectural historian Austerlitz was unsure if libraries and their tireless devotion to processes of myriad knowledge accumulation were like Islands of the Blest or like penal colonies. To me it still feels like we have sufficient freedom of action and that there are less barriers, and even though this means that some of our knowledge may be starting to become less specialised and proprietorial this is a cause for celebration rather than regret. The Web has reminded us that seeking and managing knowledge can be fun and that we don't require the same degree of centralisation and control to make knowledge management systems work. Our institutions should study this phenomenon closely and manage their assets accordingly. Meanwhile they can also learn from and participate in the shared learning space that the Web provides for that perennial concern of ours -preservation.

If all this is true, then there has probably never been a better time to start out as a 'professional audiovisual asset' but then there has probably not been a more challenging time if your job is to manage them.

Notes and references

- Peter F. Drucker. Management challenges for the 21 st century. - Oxford: Butterworth/ Heinemann, 1999. ISBN 0 7506 4456 7.

In six illuminating chapters Drucker covers management's new paradigms, new certainties, change leadership, information challenges, knowledge-worker productivity and how to manage oneself.

- Tony Brewer. "Why effective information management is needed to enable successful corporate change". In: Proceedings of the Information Management Conference (IM96), 1996, London

- To inform my understanding of Digital Asset Management for the purposes of my talk I used the following definitions to be found in

David Doering's article "Defining the DAM thing: how Digital Asset Management work" at http://www.emedialive.com/r2/2001/doering8 01 .html

Content Management: The strategy and technology for storing and indexing information from and about analog or digital media.

Data Mining: The strategy and technology for retroactively locating, retrieving, and processing information from a company's records or digital storage.

Digital Asset Management: The technologies used to locate and retrieve specific digital content objects for possible resale or re-purposing.

Knowledge Management: An overall strategy to index and retrieve information pro actively from whatever medium a company has. This differs from data mining, which is a reactive strategy.

Media Asset Management: The technologies used to locate and retrieve specific content objects from analog or digital media.)

- George Steiner. Grammars of creation. - Yale University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-300-08863-9

- W G Sebald. Austerlitz. - London: Hamish Hamilton, 2001. pp363-365

- William Matthews. "NARA seeks ideas for e-records archive" Federal Computer Week 19.8.2002 www.fcw.com/fcw/articles...

- Lorcan Dempsey, in Ariadne (22, January 2000) http://www.anadne.ac.uk/issue22/dempsey/

- Perseus Project http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/

- The Gistics Digital Asset Management Market Report 2002 ftp://access30:a30cgtx30@ftpd.5erversmiths.com/DAMMRep02Bro.l.6.pdf

- A compilation of on-line publications about Haystack can be found at http://haystack.lcs.mit.edu/literature

- From the Doc Searls weblog http://doc.weblogs.com/

- David Weinberger. Small pieces loosely joined (a unified theory of the Web).- Perseus Books, 2002

- David Winer. The history of weblogs. http://newhome.weblogs.com/historyOfWeblogs

- Tomalak's Realm, http://www.tomalak.org/

- Daypop - www.daypop.com Also www.daypop.com/top.htm lists the most popular sites connected to by webloggers.

- XML4Lib Electronic Discussion. http://sunsite.berkeley.edu/XML4Lib/

- Tim Berners Lee.The semantic web. Scientific American (May 2001) http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?articlelD=00048144-10D2-1C70-84A9809EC588EF21

- SIMILE (executive summary, public document) http://web.mit.edu/dspace-dev/www/simile/resources/proposal-2002-04/exec-summary.htm

Printable version

Photobook