3. Documentation (Roger Smither)

1. Introduction: why document?

Few, if any, established archives can truthfully claim that the documentation of their collections is satisfactory or adequate. Most will admit to a sizeable backlog of material which is at best poorly catalogued or at worst completely uncatalogued. Older archives will attribute such shortcomings to the failures or faulty priorities of previous generations of archive keepers, but enquiries about their current practice will often disclose that the backlog is not shrinking, and may not even be static. This state of affairs is also common to many archives created too recently to have previous generations of administrators to whom blame can be attributed. The truth is that it is not only in the past that cataloguing and record-keeping generally have failed to be accorded a high level of priority in archives' policy.

The reasons for this are not difficult to find. The task of cataloguing is undramatic, its only urgencies are self-imposed, and its visible benefits on the whole are unspectacular and slow to materialise. Large backlogs of uncatalogued material, after all, have not inhibited the survival of archives into the present. An archive that is not growing, an archive whose collection is not being used by its intended audience or customers, and an archive whose collection is deteriorating are all in different ways obviously failing. An archive with less than perfect documentation, on the other hand, is merely making life less easy than it might be for its staff and users -or so it seems. Hence the concentration in a new archive on building a collection, and in an established archive on the technical care of the collection and the improvement of service to users; hence, too, the repeated decision, in the face of pressure for economies, that the archive's cataloguing section is the one which may be reduced, relatively or absolutely, with least disruptive effect on the archive as a whole. Until more secure and prosperous times arrive, why catalogue?

There is more than special pleading, however, behind the argument of cataloguers that the perspective and priorities just outlined are wrong. The task of cataloguing, or rather of documentation generally, should be seen as central to all aspects of archive administration. An acquisitions policy can be effectively pursued only if the decision makers know the material already in the archive and the gaps in the collection. The work of technical care and preservation of the collection depends on adequate record keeping which, if not actually part of the cataloguing procedure, has several points of contact with it -at the simplest level, archival effort may be wasted in the unknowing care of separately acquired duplicate copies of the same recording. An adequate service to the public cannot be achieved or maintained without the provision of catalogues and indexes of high quality - the personal knowledge of archive staff is no substitute, as any archive which has lost such a human encyclopaedia to accident, illness or a new job can testify. A poorly documented archive is thus at risk in all its activities, and an inadequate cataloguing effort can only increase the level of risk.

2. The documentation needs of sound archives

The precise nature of the documentation required by an archive will depend on the type of material it collects; the requirement will also be perceived differently by the archive's staff and its outside users. In general terms, however, documentation may be considered under three headings - registration, cataloguing and indexing.

Registration

An up-to-date register or inventory of its collection is an essential administrative tool for an archive and the maintenance of such a register is therefore a high priority task, although it need not be a complex one. The process of registering an acquisition formally acknowledges - most tangibly by allotting the new item an accession number which gives it an identity within the archive - both that the collection has been augmented by a new item, and that the item is now part of the collection. The register thus provides a reflection of the archive's growth, and a starting point for all the other documentation which is likely to build up around the item.

The essential feature of an accessions register is its simplicity. Complexity invites delay or confusion, and in either of these cases the register fails to fulfill its purpose. Registers are commonly held in book form, the pages divided so that entries appear in columns under such headings as 'accession number', 'date received', 'source' (i.e. from whom received), 'method of acquisition' and 'identification' (i.e. title or description of item). Entries are obviously in accession number order. Some archives use the numbers themselves to convey information, for example by maintaining separate number runs, or reserving blocks of numbers for different types of material, or by recording each year's accessions in a new numerical run. Such practices are of dubious value they may break down (a sub-collection might grow beyond the block of numbers reserved for it) and in any case the information implied is generally available elsewhere in the documentation. A single, simple numerical sequence is on the whole the preferred approach to accessions numbering -among other benefits, it conveys a direct impression of the growth of the collection.

Individual archives will naturally vary the column headings used to register their own accessions. An archive whose material derives solely from its own staff in the field, for example, would have no need for entries under method of acquisition and source, but might substitute the name or initials of the field-worker responsible and other details such as place and date of recording. Some archives use the accessions register for additional purposes perhaps as a checklist of procedures to be followed in the acquisition/archiving/cataloguing process. Such usage does, or at least should, not violate the principle that the register is a simple document, intended as an aid to archive administration.

Cataloguing

In contrast to registration, cataloguing is a complex task, whose intended beneficiaries are both the staff of the archive and the outside users of the archive's·collection. The purpose of a catalogue is to provide, in systematic form, information on the items contained in a collection in sufficient detail to enable those who have to administer that collection or who wish to use those items to do so as efficiently as possible. Efficiency, in this context, means both the minimum waste of time and the minimum unnecessary usage of the recordings in the archive.

Information normally held in the catalogue falls into several categories, although their precise nature will obviously vary with the type of material catalogued, as is shown in the case studies at the end of this chapter. In many archives, the information categorised here is not all held in a single physical catalogue - a system of parallel files may be a perfectly acceptable alternative. It remains, however, a part of 'catalogue' information.

The first category is the formal identification of the recording catalogued: formal identification is identification made accurately within the rules and practices established by the archive, as distinct from the simple identification made at registration. What constitutes correct identification will vary with the material collected: an archive of commercial recordings will use the title that appears on the item catalogued, where an archive of wildlife recordings will use the correct scientific designation of the species recorded and an oral history collection the name of the person interviewed.

Since the formal primary identification of the recording may not actually be very informative, a major part of catalogue information consists of the elaboration of that identification. For collections of commercial recordings, this will generally approximate to the procedures traditional to the cataloguing of published material -the linking of title to statements of responsibility (i.e. the identification of composers or authors, performers, etc.). Collections of non-commercial recordings will have different priorities, depending on the nature of the material collected. Ethnomusicology recordings, for example, which may be identified in the first instance by the name of their collector, will require as additional information geographic (or linguistic or anthropological, or a combination of these) indications of the circumstances of the recording, including a date, and information on what was recorded. An archive collecting the proceedings of a national legislature would require information identifying the session (day and time), the topic and the speakers in a debate or committee, with, perhaps, reference to the published (transcribed) proceedings.

The purpose of providing this level of information is, first, to make unambiguous the identification of the recording (to establish, in other words, that an item is not merely a recording of Stravinsky's 'The Rite of Spring' but is the recording made by a particular orchestra and conductor on a specified occasion) and, second, to provide sufficient detail to enable an interested potential user to assess whether or not a recording contains material appropriate to his or her interests. Thus in the field of material culture a catalogue entry should make clear exactly which processes are being explained and from what perspective; in oral history, the catalogue links an interview to topics, and shows how the person interviewed relates to them. Reading the catalogue cannot be a substitute for using the collection, but a catalogue should ensure that the collection is not wastefully used and that the user's interests are matched to the material listened to as precisely as possible. This will commonly mean that users are guided not merely to specific recordings, but to specific sections of recordings. Lengthy items (especially those generated by field workers) are divided into sections -reels, timed passages, audibly-signalled segments -and the divisions reflected in the catalogue summary or synopsis.

Further categories of catalogue information include technical data on the recording, indicating the form in which it was first recorded and the form in which it would be made available to users. An archive covering more than one language will need to specify the language of recordings. The circumstances of the production of the recording would be included as subsidiary information when they do not form part of the full or elaborated identification; details of acquisition are similarly covered. This information overlaps into the question of copyright and other restrictions on access to, or use of, the material. Finally, an archive will wish to establish connections between the recording catalogued and related material such as further recordings, transcripts, related documents (photographs or text connected with the item catalogued) and bibliographic citations.

It will readily be seen that a catalogue entry providing all of the information suggested in this section will be a lengthy document in its own right. It will also be appreciated that by no means all of these details need (or indeed should) be available to all readers of the catalogue. This is best exemplified in the area of technical information. For the purposes of its own technical staff, and perhaps for professional or commercial users, an archive will need extensive details on the recording, including perhaps the machinery, tape and configuration used in the original recording. For a casual user, however, the knowledge that all recordings are made available on stereo cassette 'listening copies' might make the entire category of technical information redundant in a version of the catalogue provided for general access or sale. To take another example, the question of restriction may involve information confidential to the archive and the person concerned with the recording, when all a user need know is that there are (or are not) restrictions. These considerations underline the statement made earlier, that the product of the cataloguing process need not be a single catalogue. The provision of separate 'internal' and 'external' catalogues, or the supplementing of an open catalogue with restricted files of detailed technical or confidential information, would be acceptable, indeed logical, procedures. The essential qualification, of course, is that cross-reference between all sources of information be quick and precise. This is guaranteed by the use of a single unambiguous label to identify the recording wherever it is mentioned; the accession number is the obvious choice for such a label.

Indexing

In providing the information outlined in the previous section, an archive's cataloguers are only fulfilling a part of their function. If uncatalogued material is effectively useless (since an archive and its users may be unaware of its content in any but the most elementary sense, and may indeed be virtually unaware of its existence) then material on which information is solely available in an unindexed catalogue is only slightly more open to use. Knowledge of items relevant to particular needs will only be gained from such a catalogue by prolonged searching, by accidental discovery, or by a fortunate feat of memory by a member of the cataloguing staff. None of these constitutes a reliable basis for an archive's service.

Indexes and classification systems are provided to open up the archive by providing access points and channels to the information available in the catalogue and -by extension -in the collection itself. Additional access points are provided by sorting the information in the catalogue, or extracts from it, in alternative orders: thus a catalogue of classical music, catalogued by title, would usefully be supplemented by indexes of composers, performers and so on. Channels to information are provided by the establishment of a logical structure of indexing vocabulary and styles, so that cataloguers and researchers can be instructed to consider the collection in similar terms. For example, the same archive of classical music might wish to provide an index by chronological period. In such a case, the information would be directed into the channels by the decision either to name periods by actual year or century designations, or by epoch titles such as 'High Renaissance' and 'Baroque'. The nature of the decision taken is arguably of less importance than the fact that the decision is taken and consistently applied. It does not matter too much whether a period is called 'Nineteenth Century' or 'Victorian'; it matters a great deal if, on different occasions, it is called both (and a number of other names besides) so that a user looking up only one term will fail to find all relevant information.

The number and nature of the indexes provided by an archive will depend on many things, including the resources of the archive and the expectations of its users. The principal determining factor is the nature of the material collected. Archives of commercial recordings may concentrate on indexes of titles (which will require indexing, to restrict the potential confusion of catalogue titles in different languages or formats: 'Die Dreigroschenoper' and 'The Threepenny Opera'; 'Ninth Symphony' and 'Symphony No.9') and of authors, composers, performers, directors, etc. These concerns will be shared by collections of other types of music, such as ethnomusicology, but such collections will also share indexing requirements with other archives of field recordings -circumstances of recording, name of collector, and so on. Different types of field recording will have different priorities -place, for example, which is essential to collectors of dialect, linguistic and wildlife recordings, for example, is generally considered to be of only peripheral interest in oral history. Oral history and other essentially narrative recordings, however, require analysis by subject content -an area where vocabulary control and the structuring of an index are at the same time most important and most complex.

The style of index provided will also vary. In some archives and some circumstances, the preferred procedure is to reproduce effectively the bulk of the catalogue description for the relevant item at every entry in the index; in others, the index term is merely followed by a list of accession numbers for appropriate recordings. In some cases, attempts have been made to use extant bibliographic classification systems -such as Dewey or the Universal Decimal Classification -as a ready-made system of vocabulary control for subject indexing, while other archives use their own system of 'natural language' index terms. In a general chapter such as this one, there can be no real attempt to specify that any given solution is correct, or better than another: the choice between numeric classification codes and natural language, for example, is the choice between a system which comes ready-developed, but may prove difficult to use (because of the need to translate index statements and enquiries into number-strings), and a system whose development must be carefully planned and monitored but which may seem more accessible and 'friendly' to staff and users.

A final factor in the question of indexes to supplement or make accessible the archive's cataloguing effort is the provision of something like the indexing function through mechanisation or computerisation. At its most highly developed, technology may contradict the statements made in the first paragraph of this section: catalogue information may be held in a data-base which can be interrogated 'on line' via a computer terminal, so that physical indexes are not apparently necessary. A later section of this chapter will look at the topic of computer systems.

3. National and international standards

Most of what has so far been written has been written as if a sound archive will be established, and will be left to develop its documentation policy, in an atmosphere of almost complete freedom of choice. This will, of course, never be true. The material about which an archive is offering information will be considered by its users and others in a context which includes what is available from other institutions, and the documentation will consequently be planned under the pressures of precedent and example. Such pressures may come from several directions. A sound archive may, for example, be established within an institution which already contains a reference collection in other media -books, manuscript documents, photographs, film or museum objects and will then experience pressure to conform to procedures observed in extant collections. There may, for instance, be an institutional or national policy committed to usage of one of the MARC-derived systems. There will then be the pressure of example - the inclination to follow the methods of other sound archives which the new archive has been created to emulate or complement. There is, finally, the pressure of emergent international standards promoted by international groupings of appropriate disciplines - for example the International Standard Bibliographic Description for Non-Book Materials, or ISBD(NBM), published by the International Federation of Library Associations.

In many cases, the advantages of adhering to a standard will be obvious. Within an institution, for example, a unified cataloguing system would help ensure that users had access to all material relevant to their interests in several media -an instrument and a recording of how it sounds when played, an industrial machine and an explanation of its use, etc. Similarly, and especially in the field of commercial recordings, adherence to an international descriptive standard will help users discover the information that may be most important to them -that is, the extent to which one archive duplicates or fills the gaps in the collection of another.

There are, however, two potential dangers which should always cause an archive carefully to consider the full implications before accepting the use of a given standard. One is that the standard proposed may not, without change, be applicable to the medium of sound recordings; the second is that it may not be applicable to the specific type of material collected by the archive. The ISBD(NBM) may be used as an example: although designed as a framework for information exchange rather than as a system for archival cataloguing, the desirability of consistency in the documentation of commercial recordings inevitably makes ISBD a subject of great interest for cataloguers of sound material. In 1980, a joint working group of the Cataloguing Commission of the International Association of Music Libraries and the Cataloguing Committee of the International Association of Sound Archives submitted to IFLA detailed recommendations for the improvement of ISBD(NBM) as applied to sound recordings. Points requested by the working party included, for example, the elaboration of rules in ISBD(NBM) governing responsibility statements and physical description, and of cautionary notes concerning the application to sound recordings of the concepts of 'editions' and 'series'. These points are additional to those acknowledged in the ISBD itself: that it is primarily concerned with 'materials published in multiple copies' and excludes 'specimens or found objects' (which category may be taken to include field recordings), and that it 'may require elaboration' to meet the requirements of archives.

ISBD(NBM) is far from unique in any of these respects. Like it, most cataloguing standards derive from the world of librarianship, and many are, for example, not compatible with the sound archivist's perception of 'responsibility' (multiple, and shared between author and performers) as distinct from the more conventional concept of authorship. Outside the field of commercial recordings, the problem may well get worse. Geared to titles and responsibility, standards may not cater adequately for the preferred identifications of field recordings, and may not accommodate the desirable level of description for such works. While, therefore, adherence to standards is an admirable target for sound archive cataloguing, a new archive should be entitled critically to examine the specific applicability of any single proposed standard to its cataloguing needs, and to seek necessary improvements in the standard as an alternative to compromising its own practices.

4. Computer systems

A further dimension to the questions discussed in the previous section, and a topic of increasing general relevance in any case, is the possibility of the involvement of mechanisation or computerisation in cataloguing. Computers are becoming more accessible year by year: the equipment itself is becoming cheaper, and there is an increasing choice of program packages for computer applications, including cataloguing. The only dimension lacking, perhaps, is a realistic appraisal of what computer usage mayor may not really involve.

Mechanisation has always been one way of reducing the drudgery of documentation. Even at a simple level, the use of stencils or photocopies to produce multiple copies, in whole or in part, of a catalogue entry can be one way of cutting down the clerical labour of generating several index entries. Full computerisation develops this advantage a stage further by removing the task of index compilation altogether. From a properly compiled catalogue entry, a good computer system will automatically generate all the indexes required with little or no further human effort. More, it will provide selective listings to suit special needs (it may, in fact, ultimately offer the facility of 'on line' dialogue between users and the catalogue data-base, virtually removing the need for indexes altogether)J it will also facilitate, through the technology of computer type-setting, the production of published catalogues.

Inevitably, for these advantages, there is a price to pay. Indeed, there may be three prices to pay, only one of which directly involves money. That one is, of course, the cost of the system. The others are restrictions on cataloguing procedures, and the changed nature of the actual task of cataloguing.

The first two are intimately connected: in crude terms, at present, the cheaper the cataloguing package, the more compromises an archive is likely to have to accept in its procedures. Since few computer packages have so far been tailored directly to sound archive needs, a sound archive is likely to have to use a package developed for other purposes or to develop its own. Access to an extant cataloguing package may quite possibly be among the more positive inducements for a new archive to conform to an institutional or national standard. The majority of such packages, however, are those designed for library purposes, and the involvement of a computer tends to intensify those difficulties already noted in cataloguing a sound archive to a library standard: for example, a computer system may be incapable of accepting more than a set number of 'responsibility' statements or a descriptive summary of adequate length, or of generating indexes from field recording details. On the other hand, the conversion, development or design of a more suitable package is likely to require access to skills which will not be available within the majority of sound archives, and can only be brought in from outside at some expense.

The third category of price to pay is the actual nature of work involved in cataloguing. It will be remembered that when it was claimed that a good computer system could automatically generate all necessary indexes, the significant qualification 'from a properly compiled catalogue' was added. A computer system is only as good as the information entered into it, and (unless time and money is to be spent on expensive error-checking procedures within the computer) the effect is that that information must be of the highest possible degree of accuracy and consistency, and on occasions of great apparent triviality as well. Human cataloguers will recognise that 'HMV' and 'H.M.V.' and 'His Master's Voice' are effectively synonyms, but to the majority of computer systems they would be totally distinct terms; similarly, human cataloguers may cope without effort with alphabetical filing conventions concerning the ordering of numbers and abbreviations, or the ignoring of opening definite or indefinite articles, but such details must be explained in some way to the computer. The price paid for trouble-free indexing, in other words, is more troublesome cataloguing and particularly more painstaking checking and proof-reading of catalogue information.

This is not intended to sound unduly pessimistic. Several archives are successfully using computers in their cataloguing, as the case studies show. It is, however, essential to be realistic, and especially to doubt the salesmanlike claims of anyone who alleges that computerisation will be cheap, or easy, or just like conventional procedures or (as is not unknown) all three simultaneously.

5. Staff

From the points raised so far, it will appear that three areas of expertise could be appropriate backgrounds to the staff of a sound archive's cataloguing section librarianship or archivism (reflecting the priorities given to standardisation), relevant subject knowledge to the archive's areas of specialisation, and information science or computing skills.

In effect, the expertise associated with information science is not that most appropriate to the routine work of cataloguing in most sound archives, although access to such expertise (on a consultancy basis) can be of great value, especially to an archive establishing its cataloguing system. Similar arguments, it may be noted, apply to computer expertise, even for archives contemplating a computerised system. The priorities and budget of an archive are unlikely to encompass the establishment of a team of systems analysts and programmers -such a team would be severely under-employed. A single expert may be more necessary (especially, say, in an archive using a complex or on-line system) but reliance on an individual leaves an institution vulnerable to that individual's departure. It is better policy to seek to establish, with outside help as appropriate, procedures sufficiently routine for the archive's normal staff to manage.

In choosing between staff trained in librarianship or archivism and subject experts, an archive will be affected by the types of material it collects. Professional training has undoubted values, and significantly lessens the archive's own tasks in training new staff in relevant skills. On the other hand, the cataloguing of some types of sound material is likely to require abilities other than those of conventional cataloguers. Much book cataloguing consists of the interpretative transcription of information available from the book's title page; the cataloguing of many sound recordings, however, requires that the cataloguer listen to the material and provide an intelligent analysis of what is heard. Appropriate knowledge of the subject concerned is therefore of greater value than general cataloguing skill, and it may justifiably be felt that it is a shorter task to instil the principles of good cataloguing in a subject expert than to give a useful grounding in the subject to a trained cataloguer. The choice of qualifications will thus depend on the material collected and the type of cataloguing system used. An archive of commercial recordings, or of field recordings well-documented by their collectors, especially if using a library-derived cataloguing system, may justifiably select trained librarians; an archive of unique material will be better advised to look to subject experts. Individuals combining both backgrounds, of course, should be made particularly welcome.

Similar considerations dictate the answer to the question of the appropriate size for an archive's cataloguing section. The rate of growth of the archive, the cataloguing system employed, the types of use of the collection, and (in the case of an archive of field recordings) the contribution made by non-cataloguing staff are all critical factors. Those archives who supplied the examples used in the case-studies below were also asked to supply notes on staff levels: of the archives collecting primarily for research purposes non-commercial recordings, documentation staff never surpassed three, often with duties other than cataloguing, and in no case was this considered entirely sufficient; in all cases, it should also be noted, some of the burden of documentation was shared by field workers. Archives of commercial recordings can normally accommodate much larger accession rates with similar sizes of staff, but even so may feel that larger cataloguing sections would be useful. Broadcasting archives, in a world of day-by-day commercial pressure, may have documentation staffs that seem by contrast enormous: the Dutch broadcasting service NOS has in excess of 15 in its various departments. Cataloguing, it seems, remains an undervalued task except in collections that depend commercially on their ability to retrieve material from their collections. Those setting up new archives might be encouraged for their own sakes to make a more balanced assessment of priorities.

6. Case studies

Collections of oral history recordings

Case Study: Imperial War Museum, London, England.

(a) Collection

The Museum's collection comprises over 6,000 hours, 90% of which is speech, consisting mainly of oral history interviews conducted by Museum staff and of broadcast material. The remainder consists of music, sound effects, etc.

(b) Cataloguing Staff

Cataloguing is the primary responsibility of two graduate staff, who also have other duties; they receive advice from the Museum's Department of Information Retrieval. Occasional use is made of 'casual' staff (i.e. staff on short-term appointments), and increasingly of contributions to the documentation of their own interview material by oral history field workers (see gi below).

(c) Catalogue

Within the Museum, catalogue information is accessible on computer-output microfiches which replace a card catalogue. Catalogues to completed oral history projects (see gii) and to other coherent sub-collections are published as part of the Department of Sound Records' public service.

(d) Catalogue System

The sound records collection is included in the scope of the Museum's overall cataloguing policy. From 1977 to 1982, the collection was catalogued using a modified version of APPARAT, a computerised system developed by the Museum initially for its film collection. From 1983, all Museum cataloguing, including sound records, will use the computer package GOS developed by the Museum Documentation Association. Catalogue information is supplemented in some cases by transcripts and personal files.

(e) Indexes

GOS will be capable of maintaining a keyword subject index in addition to a combined index of people interviewed (including name changes etc.), and of generating other indexes at need. Short listings for completed oral history projects also provide a useful tool for visiting researchers.

(f) Example

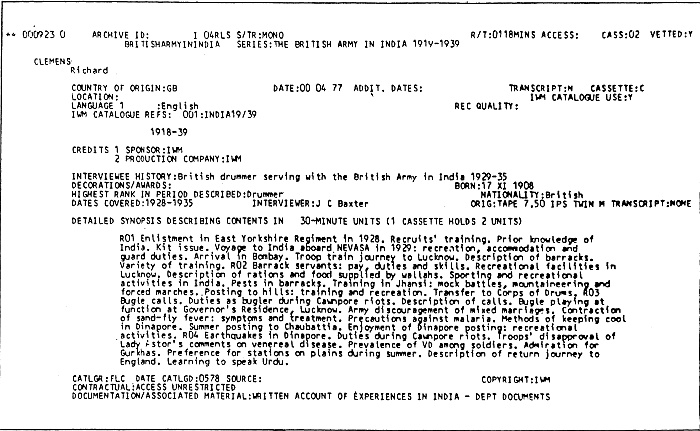

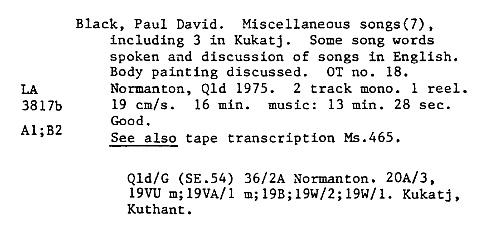

See figure 1 for a sample entry from the APPARAT microfiche; entries were arranged in accession number order.

Figure1

Figure1

(g) Comments

i. The number of cataloguers has not proved large enough to keep pace with the oral history acquisitions generated by the three interviewers on the Museum staff, and the freelance interviewers who are also employed. (There is of course also the non-oral history material). The two expedients mentioned in (b) above represent attempts to prevent the growth of a backlog of uncatalogued material.

ii. The Museum's oral history collection policy is geared to 'projects' of interviews on specific topics, and thus lends itself to the publication of catalogues to sub-collections. Compare with the relatively open-ended research orientation of, for example, the Welsh Folk Museum which forms the subject for the next case study.

Collections of folklife and language recordings

Case Study: Arngueddfa Werin Cyrnru (Welsh Folk Museum), Cardiff, Wales.

(a) Collection

The collection comprises over 3,750 hours, 85% of which is speech, consisting mainly of folklife recordings made by Museum staff.

(b) Cataloguing Staff

The ten or so members of the Museum staff who make field recordings (and who generate in all about 200 tapes per year) are responsible for preparing summaries of their own recordings. A central section of three people (one graduate, one assistant and one typist), who also have other responsibilities, manages all registration and central indexing work and prepares summaries for tapes that are not properly documented (see gi).

(c) Catalogue

A card catalogue is maintained within the Museum. There are no published catalogues.

(d) Catalogue System

The catalogue is based on two types of card: cards for speakers, arranged alphabetically and containing biographic information, and cards for interviews, arranged numerically and containing tape summaries. The card catalogue is supplemented by transcripts etc. (see gii).

(e) Indexes

The dual nature of the central catalogue makes it partially self-indexing. In addition, optical feature cards are used in a 'post-coordinate' indexing system controlled by a bi-lingual thesaurus of keywords developed by the Museum. Specialist indexes appropriate to their own research are generated by individual field workers.

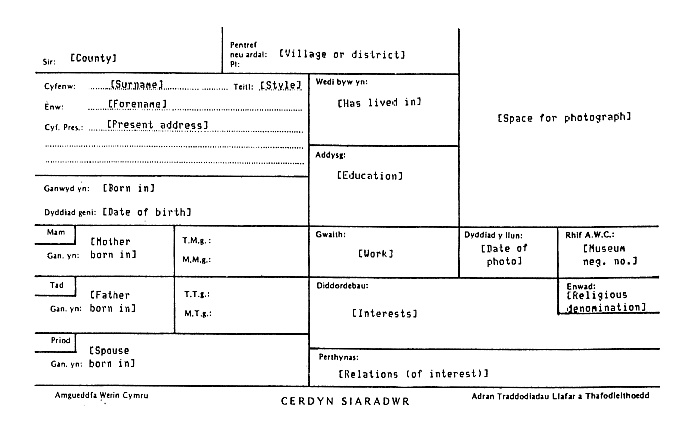

(f) Examples

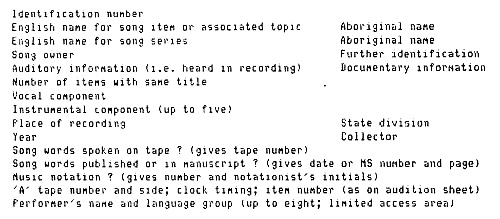

i. The front of a speaker card is illustrated in Figure 2. (Headings are in Welsh; English translations have been supplied.) The reverse of the card lists the tapes that contain interviews with the speaker, and provides spaces to describe or evaluate the speaker's suitability for interview, usage of the Welsh language, etc. Eleven headings are provided, including 'Correctness of language'; 'Sociability'; 'Memory'; ' Pronunciation'.

Figure 2

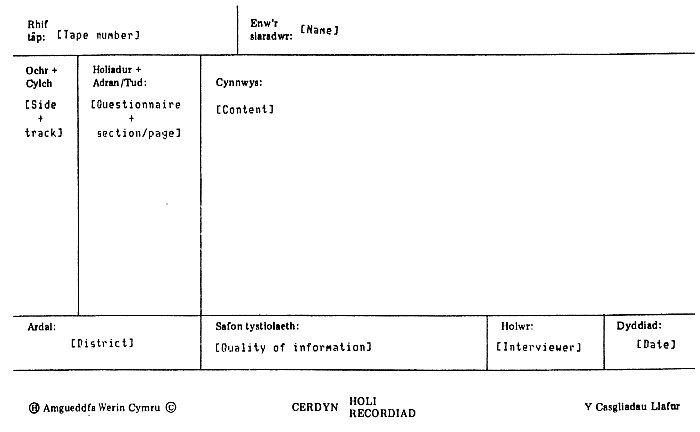

ii Figure 3 shows the front of an interview card. The reverse of the card continues the list of contents and provides space for entries on 'Place of recording'; 'Personality and atmosphere'; 'Additional voices on tape'; 'Purpose of recording'; 'Value of recording'; 'Sound quality'.

Figure 3

Figure 3

(g) Comments

i. Recordings at the Amgueddfa Werin Cyrnru represent 'research in progress' for Museum staff -as distinct from, for example, the project-based work of the Imperial War Museum. The documentation supplied by field workers is therefore analogous to research notes. The central cataloguing staff is considered to be of about the right size, although a team of this size without other responsibilities would be better still.

ii. The dual card catalogue is a clever solution to a significant problem in cataloguing field recordings (especially of speech) -their tendency to generate catalogue entries of great length, which can make the design of a single catalogue card difficult. On the other hand, this system, which also includes an accession register in which some biographic information is recorded, must involve some duplication of effort. Note also the quantity of subjective evaluation anticipated by the cards. Although quite appropriate to research notes, this sort of entry would not normally be expected in a catalogue to which there was to be much public access and in fact access to the catalogue is restricted to approved users only.

Collections of wildlife recordings

Case Study: British Library of Wildlife Sounds, British Institute of Recorded Sound, London, England.

(a) Collection

A self-contained collection within the total holding of BIRS (67,000 hours), BLOWS has some 1,000 hours or 25,000 recordings covering well over 5,000 species. The collection consists of commercial recordings, copies of BBC material and privately-made recordings.

(b) Cataloguing Staff

The collection has no cataloguing staff as such, the total staff of BLOWS is one person. Documentation of non-commercial recordings relies on notes supplied by the individual responsible for the recording; BBC material relies on BBC catalogues. Overall documentation policy at BIRS is decided at Institute level (see g).

(c) Catalogue

The collection is covered by catalogue’s maintained at the Institute on cards and data sheets and by BBC Natural History Sound Archives catalogues. BLOWS publishes discographies for commercial recordings on particular subjects (e.g. African bird sound).

(d) Catalogue System

BLOWS will come within the scope of any long-term decisions taken about the cataloguing of the collections of BIRS as a whole. For the present, BLOWS documentation remains based on manual catalogues: a card catalogue for commercial recordings, and the 'Field and editing notes' data sheets developed for completion by field recordists for private recordings.

(e) Indexes

In so large a collection with so small a staff, various expedients are used to provide finding aids. Data sheets are filed by family and scientific name of species; they are thus effectively self-indexing. A separate card index is maintained for species covered by commercial recordings. BLOWS also annotates (annually) a copy of an authoritative published checklist of bird species to create a guide to its collection. Noted as desirable for inclusion when resources and capability permit are indexes by geographical location, habitat, type of sound, recordist etc.

(f) Examples

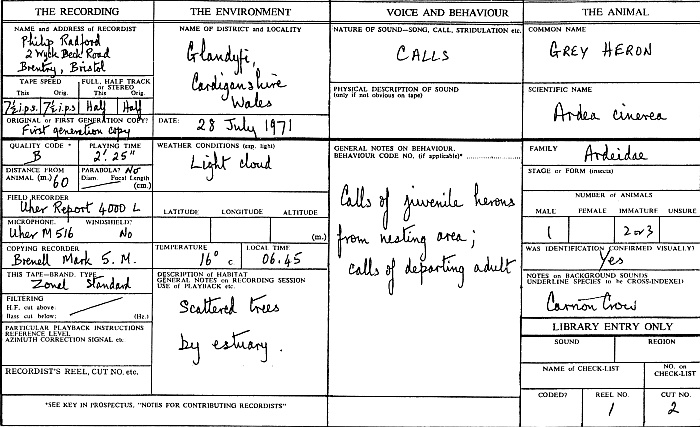

i. Field recording data sheet is illustrated as Figure 4.

Figure 4

Figure 4

ii. The draft of a format for a computer catalogue derived from Example i is shown [below].

Ardea cinerea GREY HERON

Calls. 1 adult and 2 or 3 juveniles. Identified visually. Calls of juveniles from nesting area and calls of departing adult.

Background Carrion Crow.

Glandyfi, Cardiganshire, Wales. Scattered trees by estuary.

29 July 1971. 05.45. 50 Metres distant. Microphone on branch with 100 metre lead.

2'.25". B quality. Uher 4000 Report L. Uher M.516. First generation copy.

Dr Philip Radford. Tape. 19 cm/sec. ½ track Mono.

Reel 1, Cut 2. No. 1710.

(g) Comments

BLOWS demonstrates the kinds of ingenious expedient to which a collection committed to the provision of an adequate public service may have to turn in the absence of adequate staffing. Preliminary studies for computerisation in the mid-1970s suggested that the preparation of data on the extant collection for entry into a new system would require two years' work by a specialist cataloguer. It has also been calculated that the current accession rate - approximately 1,000 private, 500 BBC and 100 commercial recordings per year, - would justify, funds permitting, one full-time cataloguer.

Collection of ethnomusicology and language recordings

Case Study: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, Australia.

(a) Collection

The Institute's collection comprises over 8,000 hours, 70% of which is speech, 30% music. Material collected by anyone awarded a research grant by the Institute (including Institute staff) is deposited as a condition of such a grant; deposits from other sources are also welcomed. A range of restrictions on the use of and access to recordings is maintained by the Institute and recorded on each contract of deposit.

(b) Cataloguing Staff

Cataloguing is the responsibility of two graduate staff, both with field work experience, and one typist. All have other duties (see gi).

(c) Catalogue

Within the Institute, a card catalogue is maintained, supplemented by access from a computer terminal inside the Institute to an on-line data base. Lists of new accessions and catalogues to coherent sub-collections are published -some in microfiche format.

(d) Catalogue System

A card catalogue is used, with entries being complemented by audition sheets (which provide a detailed, timed analysis of the contents of the tape as heard), transcripts, records on restrictions etc. (see gii). Part of the collection has been catalogued using IQL (Interactive Query Language) as a pilot project.

(e) Indexes

The manual card catalogue is indexed by location of recording, song titles and series, languages and subject codes; a file of informants' names is maintained separately, and is accessible to approved users only. Under IQL, any information field contained within a catalogue entry may be the basis of an enquiry.

(f) Examples

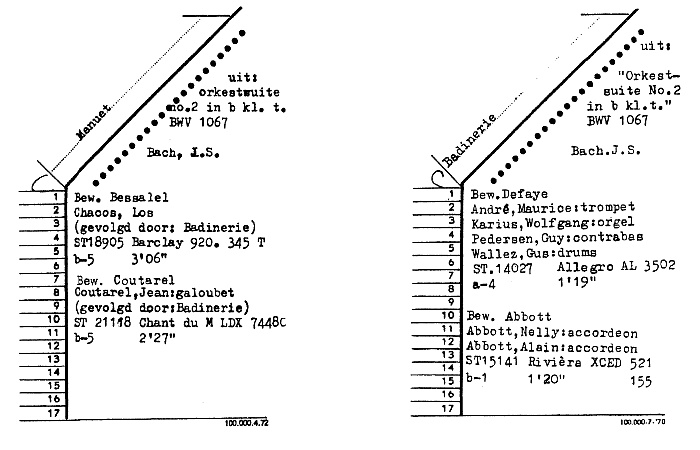

i. The catalogue card, reproduced below is filed alphabetically under collector's name. Marginal notations give tape number and restriction indicators. Library codes indicate origins (e.g. Qld/G meaning Queensland, Gulf area), content (20A/3 meaning body painting; 19W/2 meaning discussion of song and song words), and style of performance (19VU meaning unaccompanied singing by one man, 19B an elicited performance etc.). Language names are listed at the end of the codings.

ii. The fields available for a computerised catalogue record under IQL pilot project are shown in figure 7.

Figure 5 illustrates what a full catalogue entry printed out by the computer looks like.

Figure 5

Figure 5

(g) Comments

i. The number of cataloguers has not proved large enough to keep pace with accessions currently estimated at circa 1,000 tapes per year. It is thought that additional clerical and typing staff could help; schemes for training Aboriginal cataloguers have also been initiated.

ii. The use of codes to standardise variant spellings of language types and to delineate 'tribal areas', the importance given to the question of restrictions on access to recordings, the provision of a catalogue field label recognising the Aboriginal concept that songs are owned not composed, and other details visible in the examples are all conspicuous reminders of the difficulty of documenting material from different cultural traditions. The IQL format developed at AIAS is a pragmatic response to these difficulties.

Collection of commercial recordings in a broadcasting archive

Case Study: Nederlandse Omroep Stichting, Hilversum, The Netherlands

(a) Collection

In a large and rapidly growing collection, a total size is difficult to estimate. In January 1981, the collection included over 200,000 discs (about 85,500 hours, 95% music) and about 180,000 tapes (about 76,000 hours, 80% music). The main archival concern is with recordings made by NOS itself. In addition to music,

the archive has oral history, folklore and sound effects collections.

(b) Cataloguing Staff

In the commercial record department, seven of a staff of twenty employees are occupied with cataloguing tasks. The tape archive has six and the oral history department has five 'reviewers' (see gi).

(c) Catalogue

An on-premises computer-output microfiche system is in use, supplementing and increasingly replacing a card catalogue. No publications have been printed as the archive has no public role.

(d) Catalogue System

Since 1975 SYFON (SYsteem FONotheek), a computerised system, has been replacing the previous card-based catalogue. Information is stored in a format devised by NOS staff. Of particular interest is the development of an alpha-numerical classification system HOUDINI providing information on genre, period, national or linguistic origin, function etc. (see gii).

(e) Indexes

Indexes are maintained for title, composer, performer, keyword, classification and (for NOS recordings) radio licensee and date. Most indexes give full information for each recording cited.

(f) Examples

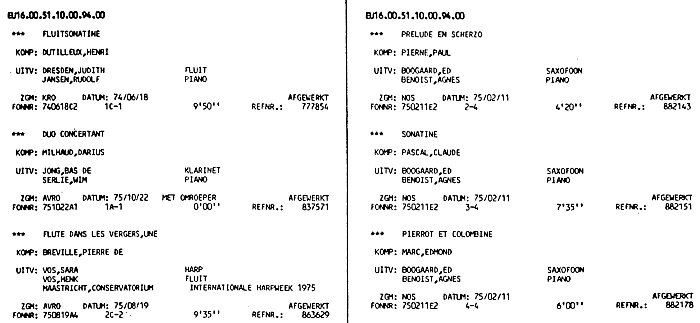

i. Figure 6 shows two cards from the superseded manual catalogue, both refer to the same principal work ('Orkestsuite No.2') but provide details of different recordings of different extracts ('Badinerie' and Menuet') from that work. Note also that two recordings are listed on each card to conserve space.

ii. Figure 7 shows representative SYFON entries which are arranged by HOUDINI classification strings (see gii).

Figure 6

Figure 7

(g) Comments

i. The documentation staff complement in the tape archive is considered large and will be reduced when work is completed on the backlog of poorly documented material. The number of 'reviewers' of oral history, on the other hand, is considered low and will be increased if possible.

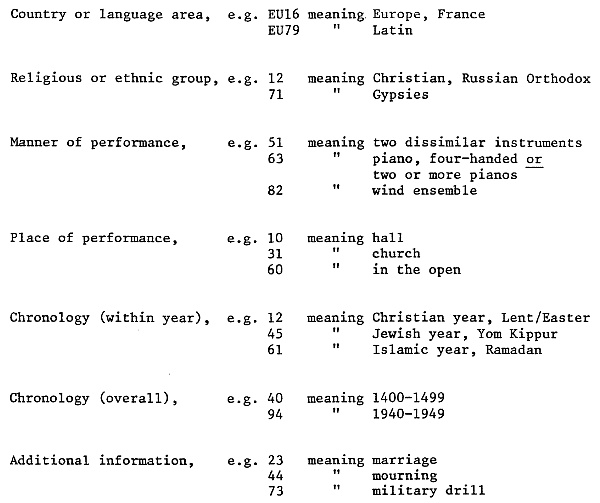

ii. HOUDINI would function best in circumstances where on-line interrogation of the catalogue was possible, but produces a useful classification/index for users even in off-line usage. HOUDINI classification 'strings' are made up of seven elements as follows:

The appearance of these strings may be seen at the top of figure 7; the strings may be decoded from the information just given. 00 is entered to indicate a 'null' entry for a given topic.